Assessment from reciprocity: a space for co-construction in training of the physical education teachers

La evaluación desde la reciprocidad: un espacio de co-construcción en la formación del profesorado de educación física

Sebastián Peña Troncoso, Sergio Toro Arévalo, Bastián Carter Thuillier, José M Pazos Couto

Assessment from reciprocity: a space for co-construction in training of the physical education teachers

Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, vol. 19, no. 61, 2024, https://doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v19i61.2104

Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia

Sebastián Peña Troncoso  *

*

Institute of Education Sciences, Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile

Faculty of Education and Culture, Universidad SEK, Chile

Department of Education, Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile

Research Program in Sport, Society and Good Living, Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile

Department of Didactics and Practice, Faculty of Education, Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

Received: 25 august 2023

Accepted: 01 march 2024

Abstract: In recent years, the assessment in the field of physical education has sparked dialogue, discussion and concern among various educational entities. This is primarily because it seems to struggle to transcend the technical rationality inherent in this didactic process. In light of this context, the present manuscript employed documentary analysis and draws from an educational experience in higher education. Its objective is to propose a perspective on the development of evaluation as a phenomenon and a proposal for reciprocal action, enabling physical education students to play an important role in shaping their learning and teaching processes. This is achieved through democratic, authentic, and reciprocal relationships that enable a discussion of the criteria, form, application, and results of a systematic educational process. We hope that this contribution serves to add to the reflections and foundations of an assessment based on authentic learning, always from a place of respect, trust, responsibility, and the democratization of knowledge.

Keywords: Assessment, reciprocity, physical education.

Resumen: La evaluación en educación física ha sido motivo de diálogo, discusión y preocupación durante los últimos años por las diferentes entidades educativas, principalmente porque no se logra superar la racionalidad técnica de este proceso didáctico. Desde este contexto, el presente artículo se realiza a través de un análisis documental y se nutre de una experiencia educativa en la educación superior, cuyo objetivo es proponer una perspectiva de la evaluación como fenómeno y propuesta de acción recíproca, permitiendo a los estudiantes ser parte importante en la configuración de sus procesos de aprendizaje y enseñanza, a través de relaciones democráticas y auténticas, que permitan discutir los criterios, formatos, estrategias y los resultados del proceso evaluativo desde una relación horizontal entre el profesorado y los estudiantes. Esperamos contribuir a la reflexión y debate de los fundamentos que posibiliten una evaluación basada en el aprendizaje auténtico, el respeto, la confianza, la responsabilidad y democratización del conocer.

Palabras clave: Evaluación, reciprocidad, educación física.

Introduction

Assessment as a subject and an integral part of formal education stands out as one of the most significant and fundamental pillars of both curricular development and the didactic processes of any pedagogical education program (Santos-Guerra, 2016). Assessment processes vary in scope, levels, and intensities. Educators are constantly assessing their students. Each teacher assesses their subject, teachers are also subject to assessed, students assess both their peers and teachers, they engage self-assess, and in some instances, the processes themselves are assessed (Lopez-Estevez, 2014). Evidently, all participants within the education system are deeply engaged in ongoing assessment processes (Peña & Toro, 2022). Nonetheless, the consistent lack of dialogue in the didactic process has led to a reductionist perspective of assessment (Hernández & Velázquez, 2004). This perspective portrays assessment as a unidirectional process (Prieto, 2015), where the teacher is the one who proposes models, develops assessment procedures, forms and instruments, omitting or relegating dialogue to the background, even though dialogue is the fundamental pillar of learning.

Within the realm of didactics, educational assessment constitutes a fundamental component of the intricate and evident connection linked to the acquisition of specific tasks, understanding, and attitudes and dispositions (Toro et al., 2015; Toro et al., 2020), thus laying the foundation for various scenarios, events, incidents, elements and moments between the educators and learners (Quintar, 2009). Even so, the term “educational assessment” remains a complex concept in its interpretation, primarily because assessment is considered a polysemic term that has different epistemic aspects. On the one hand, we have technical rationality, understanding assessment essentially as a control mechanism (Mendez, 2005; Scriven, 1967). The problem with this model is that students become passive learners (Moreno-Olivos, 2016) and do not engage with their learning and teaching processes, once again perpetuating processes fundamentally because of a neoliberal ideology, where the main actors in education refuse an open, participative democracy (Maclaren, 2012: Mclaren et al., 2010). On the other hand, we have practical rationality, which is centered on dialogic value placement and construction processes, characterizing and emphasizing the participation of the actors involved as a radical occurrence in learning, but above all in the definition, at least in its formal sense, which settles or falls outside the process generated from the assessment (Ahumada, 2005; García, 2016; Santos-Guerra, 2016). In this sense, the assessment is understood as the value placed on an observed event, based on data obtained by any defined means, a process where dialogue and the value placed on the subjectivities of all the actors involved is fundamental (Castejón, 2007).

Addressing the concept of “value placement” is significant as assessment inherently involves articulating an opinion, and this subjectivity leans toward being “objective” or “subjective” depending on the nature of the assessment undertaken. It originates from actions driven by beliefs, which may hold varying degrees of consistency (Maturana, 2018), grounded in shared and well-informed criteria coherence and transparency. Therefore, assessment in education is in fact not objective, neutral or impartial. It is more appropriate to define it as a subjective and intersubjective value placement process, product of the same didactic relationship that has been generated, sustained in the coherence, clarity and transparency of processes lived. In other words, the acceptance of subjectivity and intersubjectivity as part of any assessment process is essential, although logically this assessment should not be whimsical or improvised and it certainly shouldn’t be ill-intentioned.

Viewed through these lenses, assessment becomes a process focused on collecting, processing, and delivering accurate, dependable, and timely insights into the worth, authenticity, and significance of a student’s learning. This culminates in value judgment that paves the guide decision across multiple tiers (Ahumada, 2005). Typically, educators, concerned with assessment’s precision and structure, make these decisions. Nonetheless, these particular educational practices within physical education classes persist in upholding the one-sided nature of a didactic and thus evaluative process, which contradicts the very essence and encounter of learning. This often necessitates bidirectional processes, where dialogue facilitates the interaction among all participants in the process, accommodating their subjectivities. As a result, assessment transforms into an arena where intersubjective value placement emerges. In short, it is evident that traditional assessment practices considerably limit the freedom or autonomy of those who learn, placing greater importance on elements of a technical nature, to the detriment of dialogue and the social construction of pedagogical processes.

Embracing learning conception unique to the Biology of Knowing (Maturana, 2018; Maturana & Varela, 1994), and the “Enactive approach” (Brinkmann et al., 2019), the learning process invariably unfolds withing the organism or agent engaged in this progression. In other words, living beings in general, and humans in particular, are not “instructable,” even though they are always learning. This phenomenon occurs because of the evolution and display of each person’s actions, in a structural connection with their environment. This shapes the objects, the self and above all, the coordination of actions with other living beings of the same species and of others, in a situated emotional flow. Although there may be disruptions in the environment that trigger structural changes and consequently behavioral changes, not everything that changes depend on the shape and size of the disruption, but rather on the determinations and properties of what we are as living beings. Because of this, no two learnings are alike, although an observer (educator) may want to record and measure them the same way.

In this context, as mentioned earlier, a being is not fundamentally “instructable”, but rather adaptable. Through their interaction with the environment, they acquire the essential abilities to situate themselves and express their traits within the given circumstance (Maturana & Varela, 1994). Consequently, individuals draw from the relationships they encounter, extracting what is necessary to sustain and advance themselves within these connections or others where they hold emotional investment or interest. Thus, the most fitting form for the learning environment is that of dialogue (Maturana & Davila, 2015). This perspective is ingrained in Latin American indigenous cultures, such as The Mapuche exemplified by phrase “Kishu kimkelay ta che”, signifying ‘no person knows or learns alone, by themselves” but rather in collaboration with others, drawing upon their historical legacy (Ferrada et al., 2014, p. 35). Hence, for assessment to truly become a facet of learning, it should emerge from reciprocity, independent of it explicit purposes, as each individual learns based on their potentials and involvements within the relationship; a mutual exchange between teachers and students (Freire & Faúndez, 2013).

From this perspective, it becomes evident and paramount to recognize the profound formative significance that reciprocal assessment holds within learning processes, particularly within preservice teacher education (Trigueros et al., 2020). During this phase, prospective educators should encounter and manifest their learning via assessment, shaping their future teaching approaches:

“Tell me how you assess, and I will tell you what society you are building. The way we assess inexorably marks our students, at school and throughout their lives, and thereby contributes to creating one society or another” (Murillo & Hidalgo, 2015, p. 5).

This underscores the importance of instilling the pressing need for physical education teacher training to guide its assessment processes towards a space of co-construction, establishing ongoing consensus based on the learning process of students, teachers and the learning and teaching process itself. From this point of view, the aim of the manuscript is to propose a perspective of evaluation as a phenomenon and a proposal for reciprocal action, allowing students to be an important part in the configuration of their learning and teaching processes, through democratic and authentic relationships, which allow the discussion of criteria, formats and strategies through a horizontal relationship between teachers and students.

Reciprocal Assessment as a Didactic Process

Building upon the aforementioned, and as witnessed in recent years, assessment has garnered attention within diverse curricular models (López, 2006). This is largely due to an endeavor to shift away from a reductionist, transactional and technically oriented perspective solely focused on instructional procedures. Instead, there’s and aspiration to embrace a spectrum of variables that acknowledge education as a multidimensional process. This encompassing view not only includes learning but also incorporates formative, expressive, and therapeutic facets, alongside fostering relation autonomy. In fact, this progression should rest upon dialogue, comprehension, and continual refinement (Santos-Guerra, 2016). It should further embrace an explicit political, ethical and cultural commitment on the horizon, which is generated not from the ethics of discourse, but from the ethics of the relational experience (Dussel, 2020).

In this context, there has been an increase in the use of formative assessment (focusing on feedback for learning), self-assessment or shared assessment learning processes and authentic assessment based on competencies or performance (Ruiz & Serra, 2017). However, it seems that this falls short in moving past the technical rationality of assessment. Rather, there is a kind of tranquility or illusion of participation or “democratization” of the assessment process (Peña & Toro, 2023), but deep down it does not produce a substantive change in either the explicitation of authentic learning or in specific decision-making regarding the qualification of the class as a whole.

Deep down, there are no substantial changes in terms of the redistribution of power when carrying out assessment processes, nor are there changes towards the promotion and participation of a truly egalitarian dialogue between all parties involved. Contrarily, what comes into view are improvements in a parametric assessment system, based on the capacity and visualization of expert knowledge represented by the role of teaching, rather than a shared, consensual and co-constructed process, both of the learning and teaching process in particular and of the class and the curriculum in general.

It is common knowledge that one learns what one wants to or is interested in, based on one’s context, regardless of what is deliberately instructable. However, in this process, the way in which assessment is understood and implemented usually ends up modeling and conditioning the genuine learning interests of each person. Eventually, students end up adapting and submitting to the priorities imposed by whoever holds the power at the time of the assessment, who is generally the teacher. This situation is recurrent and usually translates into demotivation and lack of meaning in the exercise of knowing for students, who must also experience forms of relationship that are not based on reciprocity. In other words, relationships are explicitly generated around learning and grading, without considering that what is learned itself is the context instead of the stimuli (Freeman, 2007). Therefore, there are many aspects to consider in this process, but our critical issue points to the need to create spaces that enable teachers in training to make decisions regarding their assessment process, course development, and also regarding the relational dynamics that enable dialogue between peers and with the teacher.

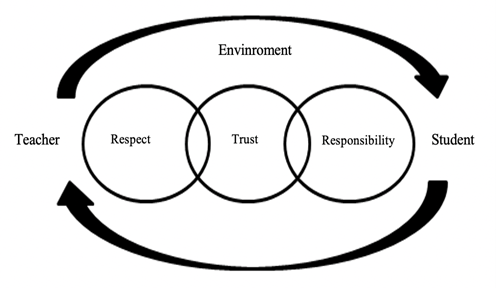

This doesn’t mean handing over total responsibility to the students, but rather clarifying the responsibility of their own learning and teaching process, reciprocally sharing the different dimensions of assessment, performance and implementation of a course, especially as teachers who take on such tasks as part of their own training. This may involve generating their own categories, appreciation scales and, above all, explicitly and collectively self-assessing their training process and that of the teacher. This approach to reciprocal assessment can be considered a process that generates changes, with the potential to promote social transformation, focused on generating spaces of reciprocal recognition between the subjects that participate in the learning and teaching process, giving each individual confidence and a voice, in an environment of respect throughout the entire didactic process, which is understood as a continuous process, beyond the three traditional moments of evaluation (beginning, process and end). In other words, we refer to assessment as a space for the recognition and development of a democratic praxis, where power is no longer centered on a single individual, thus turning assessment practices into an issue related to the redefinition of relationships (of power) and social justice (Mcarthur, 2019). At this juncture, it seems critical to us that the reciprocal assessment process must be subject to the establishment of relationships of respect, trust and responsibility (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Reciprocal assessment

This form of assessment is based on the culture of sharing ways of constituting knowledge, where ways of knowing are shared. Reciprocity is the value of taking responsibility, where we take responsibility as parts of a situated context, not as radically disconnected or isolated beings. It is quite the opposite, because the relationship is the starting point for the connection and the exchange generated by the particularities and differences that constitute both personal and social identity. In specific education terms, teaching only emerges out of learning (Freire & Faúndez, 2013), i.e., good teachers continually learn in each class that they teach or are responsible for, but rarely is that learning visibly explicit or considered as the meaning or objective of the class. Also, from the point of view of students or trainees, what they show or teach both their peers and the teacher is not a common element within class planning or management (a very relevant aspect within teacher training). Furthermore, their assessment of the class and the teacher, which is usually anonymous and not informed in terms of results, is based on control and mistrust.

A human being’s learning cannot be a phenomenon of adaptation to the environment, but rather the consequence of the epigenesis of the organism with conservation of its organization in a particular environment in which conservation and adaptation have been the operational references for the pathway followed by the same learning (Maturana, 2018). The organism is where it is because it maintained its organization and adaptation in a changing or static environment, and we say that it learned because, comparatively, we see that its current behavior is different from its previous behavior, in a way this is contingent on its history of interactions. Without a historical base of comparison, we cannot say anything. We can only see an organism in behavioral congruence with its current environment (Maturana, 2018, p.49).

In this sense, as expressed by Freire (2006), in an educational or pedagogical environment all those who participate learn. The issue is how we are explicit, in our operation as living beings in a certain environment, regarding the recognition and distinction of differences in the evolution that we display, both as learners and teachers (Maturana, 2018).

Consequently, the constructivist orientation of reciprocal assessment should not break from the conceptualization and configuration schemes of power in micropolitics that is displayed in the classroom, session or didactic encounter. This involves transiting from a traditional scheme, where the teacher proposes and decides based on the attainment of objectives or learning skills, to a dynamic of construction and reciprocal development on all didactic levels, namely planning, display, assessment and analysis (Toro et al., 2020).

If we take this option, we will not only have different results in learning the necessary and functional aspects of the teaching professionalism, but also, and above all, we will enter into a type of relational coexistence based on trust, respect and responsibility for the discipline and teaching condition. This understands it as a collective process, which does not sidestep the personal process, but concretizes and enhances the collective and community aspects.

This can be seen in the empirical evidence that is developed in and from indigenous communities in Chile, through communicative assessment in vulnerable contexts with students and their families (Pino-Sepúlveda & Montanares-Vargas, 2019). Although these educational experiences are very enriching as learnings, the Chilean curriculum is characterized by a marked monocultural rationality, which does not provide a space for epistemic pluralism, thus denying the knowledge and ways of knowing of indigenous peoples, as well as the forms that these groups consider valid for learning and assessing this learning. This is why it is essential for the teacher training curriculum to include the cultural and family ways of knowing of the Mapuche people, so that the teachers who work in these contexts can generate a dialogue between school and Mapuche knowledge (Quilaqueo et al., 2015).

The Reciprocal Assessment Experience in Health and Physical Education Teacher Training

The public policies supported by Pre-service Teacher Education in Chile (PTE or FID for its acronym in Chile) through Law 20,903 from 2016 on teacher professional development and Decree 67 from 2018 (Mineduc, 2018), on assessment, qualification and promotion in school, have led to structural changes in the country’s public policies. These give it a formative intentionality and focus on learning (setting aside the classic concept of certification) through tools that allow the student to participate in the assessment, even allowing the teacher to adjust their plans as a result of these assessment opportunities.

Despite all these changes in public policies, it is common for physical education classes to have assessment that are more about certification than training processes. This encourages the construction of a passive, conformist and dependent student body, very contrary to the real value of assessment as key in the learning and teaching process. Authors (López-Pastor & Pérez- Pueyo, 2017) indicate that “in the classrooms, faculties and corridors of educational centers, usually when teachers use the term “assessment” they are referring to the “grading” process. This happens essentially because it is what they have experienced for more than 15 years as primary, secondary and university students ... And it is what they continue to experience throughout their professional career as teachers. But insofar as we are unable to understand assessment and grading as two clearly different processes, it will be impossible to change our professional practice” (López-Pastor & Pérez-Pueyo, 2017, p. 34-35). This repeats despite studies that show the futility of this grade in the learning and teaching processes (Ibarra-Sáiz et al., 2012).

Another discrepancy in the assessment is shown in different studies (Gutiérrez-García et al., 2013; Mínguez & Aguilar, 2014), where often the teaching staff claims to carry out a formative assessment and the students state that they have experienced grading processes as part of tests and final exams (Muñoz et al., 2012).

Reciprocal assessment can lead to a concrete change in the paradigm and display of teachers in training, by allowing them to co-construct their learning and teaching processes through assessment and having the direct responsibility of contributing to the improvement of educational processes managed by their teacher educators. As a diagnostic experience with physical education students in training at a university in southern Chile, students have been able to conduct their training processes through assessment, generating ongoing dialogues and discussions with their peers and teachers, elaborating their own assessment procedures, developing instruments that not only make it possible for them to assess each student’s process, but also that of classmates, the teacher and the learning and teaching process itself, through the use of strategies and didactic resources for a given context (Beltrán et al., 2018).

This dynamic was operationalized from ongoing dialogue, using non-parametric strategies, such as the use of thematic films on real events, climate change problems with a direct effect on current daily life, the direct experience and evolution of teachers in training, in relation to nature, education and culture. Their opinions and considerations by virtue of the coherence of what was taught with the attitude and direct testimony of the teacher trainers through the meanings and performances of the course were transmitted in logbooks that delved deeper, providing a reflection or criticism of the different topics raised in each class.

Another important decision in this didactic process is the free choice of presentation formats for the learning developed on the central themes, which in turn were also chosen according to group interest. Finally, the assessment of the dynamics and types of relationships developed by the teachers of the subject in particular and as a group (ways of being and engagement between teacher trainers) was consensual, allowing a reciprocal process between teacher and students.

The challenge of this evaluative educational experience is to be able, on the one hand, to engage students with democratic practices in teaching environments that favor responsibility and autonomy (Vera & Moreno, 2016), since schools and universities do not currently facilitate student learning and participation (Calvo, 2014), but rather they are concerned about content and a possible grade. This is what leads to the need to transform a mechanical (Tobár et al., 2019) and technocratic (Moreno & Medina, 2012) process into a participatory one with much more dialogue, through three fundamental elements (respect, trust and responsibility) of learning in a relationship, where the emphasis is not on the position of each person, but in relation to others, i.e., in reciprocity, as is the case with education (Biesta, 2014).

The involvement of students in assessment is key to improving their learning (Brown, 2015), and an adequate assessment system in physical education classes can enable the discipline to overcome the physical test or exam culture, paving the way for an assessment culture with a shared and formative nature (Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2021; Santos-Pastor et al., 2019). These didactic processes will be essential in the transferability of the future teaching practices of graduates (González et al., 2021; Molina-Soria et al., 2019), improving assessment processes not only in the field of PTE, but also in the school context.

Conclusions

Reciprocal assessment represents a proposition seeking to transcend the unilateral perspective of education assessment, particularly in the training of physical education teachers. This approach enabling students to wield play a significant influence in shaping their own learning and teaching processes. This empowerment is achieved through democratic interactions and within a political, ethical and societal framework centered on reciprocity. Undoubtedly, this educational phenomenon stands as a essential element for enhancing classroom methodologies, refining teacher training, optimizing study programs, and, most importantly, improving student learning.

Reciprocal assessment, functioning as a didactic act is a relationship of trust, through a sincere dialogue that makes it possible to discuss criteria, the form, application and results of a systematic educational process. This trust extends not solely to the individuals involved but also encompasses broader to educational processes. In essence, an education built on trust implies focusing on the learning itself, rather than on the control of other aspects that are confused or disrupted with learning, and with this we refer to attendance, group control and power-based authority. Undoubtedly, this proposition heralds a significant opportunity to transition toward markedly more democratic educational methodologies. This is particularly pertinent in an era where both society and educational settings are fervently advocating for equality and equity. While the transformations of this didactic process are slow (Biggs, 1999; Brown & Glasner, 1999; Knight, 2005) and complex (Algozzine et al., 2004; Emery et al., 2003). That is why, we must generate these spaces with teachers in training, mainly because teacher training is an optimal context to transform evaluation practices, regardless of the country in which it is carried out. Initiating this transformation should entail reevaluating the prior notions that’s aspiring educators hold regarding assessment (Perez-Pueyo et al., 2016).

Finally, future physical education teachers expressed that the class was more than a traditional class. Rather, it became a transformative experience, centered on the relationship between human beings, people with life experience, in search of a professional development that is connected to and coupled with their environment and culture from an ethical, epistemic and political point of view. From this perspective, we believe that this transformative experience is a great strength for the future practices of preservice teachers.

Ethics Committee Statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by Fondecyt-ANID projects No. 11190537, 1230609, 11201036 and PIDU Project Number: DEP202207 University Austral de Chile.

Authors' Contribution

All authors have contributed to the development and revision of the manuscript and agree to the publication.

Data Availability Statement

The availability of data is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID), Chile.

References

Ahumada, P. (2005). La evaluación auténtica: un sistema para la obtención de evidencias y vivencias de los aprendizajes. Perspectiva Educacional, Formación de Profesores, (45), 11-24. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3333/333329100002.pdf

Algozzine, B., Gretes, J., Flowers, C., Howley, L., Beattie, J., Spooner, F., Mohanty, G., & Bray, M. (2004). Student evaluation of college teaching: a practice in search of principles. College Teaching, 52(4), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.52.4.134-141

Beltrán-Veliz, J., Aburto, B., & Peña, S. (2018). Prácticas que obstaculizan los procesos de transposición didáctica en escuelas asentadas en contextos vulnerables: desafíos para una transposición didáctica contextualizada. Revista Educación, 42(2), 335-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v42i2.27571

Biesta, G. (2014). ¿Medir lo que valoramos o valorar lo que medimos? Globalización, responsabilidad y la noción de propósito de la educación. Pensamiento Educativo, 51(1), 46-57. https://doi.org/10.7764/PEL.51.1.2014.17

Biggs, J. (1999). Teaching for Quality Learning at University. Open University Press.

Brinkmann, M., Türstig, J., & Weber-Spanknebel, M. (2019). Leib-leiblichkeit-embodiment. Pädagogishe perspektiven auf eine phänomenologie des leibes. Springer-Verlag.

Brown, S. (2015). Learning, teaching and assessment in higher education: global perspectives. Palgrave-MacMillan.

Brown, S., & Glasner, A. (1999). Assessment matters in higher education. Open University Press.

Calvo, C. (2014). Educación y democracia: ¿relación educativa o escolarizada? En A. Moreno y M. Arancibia (Eds.), Educación y Transformación Social: Construyendo una Ciudadanía Crítica. Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso.

Castejón, F. (2007). Evaluación de programas en ciencias de la actividad física. Síntesis.

Dussel, E. (2020). Siete ensayos de filosofía de la liberación. Hacia una fundamentación del giro decolonial. Trotta.

Emery, C. R., Kramer, T. R., & Tian, R. G. (2003). Return to academic standards: a critique of student evaluations of teaching effectiveness. Quality Assurance in Education, 11(1), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880310462074

Ferrada, D., Villena, A., Catriquir, D., Pozo, G., Turra, O., Schilling, C., & Del Pino, M. (2014). Investigación dialógica-Kishu Kimkelay Ta Che en educación.Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 13(26), 33-50. http://www.rexe.cl/ojournal/index.php/rexe/article/view/32

Freeman, W. (2007). Dinámicas no lineales e intencionalidad: el rol de las teorías cerebrales en la ciencia de la mente. In A. Ibañez y D. Cosmelli (Eds.), Nuevos Enfoques de la Cognición. Redescubriendo la Dinámica de la Acción, la Intención y la Intersubjetividad. Universidad Diego Portales de Chile.

Freire, P. (2006). Pedagogía de la autonomía. Saberes necesarios para la práctica educativa. Siglo XXI.

Freire, P., & Faúndez, A. (2013). Por una pedagogía de la pregunta. Siglo XXI.

García, L. (2016). La evaluación en la educación física escolar. Kinesis.

González, D. H., Arribas, J. C. M., & Pastor, V. M. L. (2021). Incidencia de la formación inicial y permanente del profesorado en la aplicación de la evaluación formativa y compartida en educación física. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 41, 533-543. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i41.86090

Gutiérrez-García, C., Pérez-Pueyo, Á., & Pérez-Gutiérrez, M. (2013). Percepciones de profesores, alumnos y egresados sobre los sistemas de evaluación en estudios universitarios de formación del profesorado de educación física. Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte, 2, 130-151. http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/23757

Hernández, J., & Velázquez, R. (2004). La evaluación en educación física. Investigación y práctica en el ámbito escolar. Graó.

Ibarra-Sáiz, M. S., Rodríguez-Gómez, G., & Gómez-Ruiz, M. Á. (2012). La evaluación entre iguales: beneficios y estrategias para su práctica en la universidad. Revista de educación, 359, 206-231. http://hdl.handle.net/11162/95239

Knight, P. (2005). Calidad del aprendizaje universitario. Narcea.

López-Pastor, V., & Pérez-Pueyo, A. (2017). Evaluación formativa y compartida en educación: experiencias de éxito en todas las etapas educativas. Universidad de León.

López-Estévez, R. (2014). Paradigmas y fundamentos de la evaluación en educación física: retrospectiva y prospectiva. E-motion. Revista de Educación, Motricidad e Investigación, (2), 53-77. https://core.ac.uk/reader/60658448

López, V. (2006). La evaluación en educación física. Revisión de los modelos tradicionales y planteamiento de una alternativa: la evaluación formativa y compartida. Miñó y Dávila.

Maclaren, I. (2012). The contradictions of policy and practice: Creativity in higher education. London Review of Education, 10(2), 159-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460.2012.691281

Maturana, H. (2018). Desde la biología a la psicología. Editorial Universitaria.

Maturana, H., & Davila, X. (2015). El árbol del vivir. MPV Editores.

Maturana, H., & Varela, F. (1994). De Máquinas y Seres Vivos. Una teoría sobra la organización biológica. Editorial Universitaria.

Mcarthur, J. (2019). La evaluación: una cuestión de justicia social: Perspectiva crítica y prácticas adecuadas. Narcea.

Mclaren, P., Huerta., L., & Rodríguez, M. (2010). El cambio educativo, el capitalismo global y la pedagogía crítica revolucionaria. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, (15), 1124-1130. http://eprints.uanl.mx/2195/1/revista_de_COMIE_traduccion_de_Mclaren_indizada.pdf

Méndez, A. (2005). Hacia una evaluación de los aprendizajes consecuente con los modelos alternativos de iniciación deportiva. Tándem: Didáctica de la Educación Física, 17, 38-58.

Ministerio de Educación (2016). Crea El Sistema De Desarrollo Profesional Docente y Modifica Otras Normas (Ley, N. 20.903). Ministerio de Educación de Chile. https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1087343&idVersion=2019-12-21&idParte=9690838

Ministerio de Educación, (2018). Orientaciones para la implementación del decreto 67/2018 de evaluación, calificación y promoción escolar. Ministerio de Educación de Chile. https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1127255

Mínguez, M., & Aguilar, G. (2014). Profesorado y egresados ante los sistemas de evaluación del alumnado en la formación inicial del maestro de educación infantil. RIDU, 8(1), 2. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4898827

Molina-Soria, M., López-Pastor, V. M., Pascual-Arias, C., & Barba-Martín, R. A. (2019). Ejemplo de buena práctica de evaluación formativa y compartida en la formación inicial del profesorado de educación infantil. Revista de Innovación y Buenas Prácticas Docentes, 8(1), 69-86. https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/handle/10324/53833/Ejemplo-de-buena-practica-de-evaluacion-formativa-y-compartida.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Moreno-Olivos, T. (2016). Evaluación del aprendizaje y para el aprendizaje: reinventar la evaluación en el aula. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Moreno, A., & Medina, J. (2012). Escuela, educación física y transformación social. Estudios Pedagógicos, 38, 7-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052012000400001

Muñoz, L., Oliva, F., & Pastor, M. (2012). Diferentes percepciones sobre evaluación formativa entre profesorado y alumnado en formación inicial en educación física. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 15(4), 57-67. https://revistas.um.es/reifop/article/view/174811

Murillo, F., & Hidalgo, N. (2015). Dime cómo evalúas y te diré qué sociedad construyes. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 8(1), 5-9. https://revistas.uam.es/riee/article/view/2972/3192

Peña, S., & Toro, S. (2022). Hacia una evaluación recíproca en la formación inicial docente. In C. Sanhueza, C. Diaz, y C. Espinoza (Eds.), La Formación Inicial Docente: Desde la Interdisciplinariedad en Chile. Universidad de Concepción.

Pérez-Pueyo, Á., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Fernández-Río, J., Calderón, A., García López, L. M., & González-Víllora, S. (2021). Modelos pedagógicos en Educación Física: Qué, cómo, por qué y para qué. Universidad de León. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=855350&orden=0&info=open_link_libro

Pino-Sepúlveda, M., & Montanares-Vargas, E. (2019). Evaluación comunicativa y selección de contenidos en contextos escolares vulnerables chilenos. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 21. http://dx.doi.org/10.24320/redie.2019.21.e03.1984

Prieto, A. (2015). Los paradigmas de evaluación en Educación Física. Multiárea. Revista de Didáctica, (7), 110-130. https://revista.uclm.es/index.php/multiareae/article/view/665/756.

Pérez-Pueyo, Á. P., Alcalá, D. H., & García, C. G. (2016). Reflexión sobre la evaluación en la formación inicial del profesorado en España. En búsqueda de la concordancia entre dos mundos. Revista Infancia, Educación y Aprendizaje, 2(2), 39-75. https://doi.org/10.22370/ieya.2016.2.2.593

Quilaqueo, D., Quintriqueo, S. & Riquelme, E. (2015). Identidad profesional docente: profesores de pedagogía en educación básica intercultural en contexto mapuche. In Quilaqueo, D., Quintriqueo, S., & Peña, F (Eds.). Interculturalidad en Contexto de Diversidad Social y Cultural. Universidad Católica de Temuco.

Quintar, E. (2009). La enseñanza como puente a la vida. Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Ruiz, M., & Serra, V. (2017). Coevaluación o evaluación compartida en el contexto universitario: la percepción del alumnado de primer curso. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 10(2), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.15366/riee2017.10.2.001

Santos-Guerra, J. (2016). La evaluación como aprendizaje. Cuando la flecha impacta la diana. Narcea.

Santos-Pastor, M. L., Martínez -Muñoz, L. F., & Cañadas, L. (2019). La evaluación formativa en el Aprendizaje-Servicio. Una experiencia en actividades físicas en el medio natural. Revista de Innovación y Buenas Prácticas Docentes, 8, 110-118. https://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10396/18968/innovacion_y_buenas_practicas_docentes_10.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Scriven, M. (1967). The Methodology of Evaluation. In R. W. Tyler, R. M. Gagne & M. Scriven (Eds.), Perspectives of Curriculum Evaluation Chicago (pp. 39-83). Rand McNally.

Tobar, B., Gaete, M., Lara, M., Pérez, A., & Freundt, A. (2019). Teorías implícitas y modelos de formación subyacentes a la percepción de rol del profesor de educación física. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deportes y Recreación, 36(36), 159-166. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v36i36.66532

Toro, S., Arteaga, A., & Paredes, C. (2015). Corporeidad y aprendizaje auténtico, dinámicas relacionales en contexto de la motricidad escolar. En A. Correa y F. Mizuno (Orgs.), Motricidad escolar (pp. 59-78). CRV Editorial.

Toro, S., Pazos-Couto, J., & Moreno, A. (2020). La planificación y programación de actividades en Educación Física. En: E. Martinez-Figueira y M. Raposo-Rivas (Eds.), Kit de supervivencia para el practicum de educación infantil y primaria. Universidad de Vigo.

Trigueros, C., Rivera, F., & Moreno, A. (2020). The Big Bang Theory o las reflexiones finales que inician el cambio. Revisando las creencias de los docentes para construir una didáctica para la Educación Física Escolar. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deportes y Recreación, 37(37), 710-717. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v37i37.74175

Vera, J., & Moreno, A. (2016). Razones intrínsecas para la disciplina en estudiantes adolescentes de Educación Física. Educación XXI, 19(2), 317-335. http://dx.doi.org/317-335.10.5944/educXX1.16469

Author notes

* Correspondence: Sebastián Peña Troncoso, sebastian.pena@uach.cl

Additional information

Short title: Assessment from reciprocity in the training of physical education teachers

How to cite this article: Peña-Troncoso, S., Toro-Arévalo, S., Carter-Thuillier, B., & Pazos-Couto, J.M. (2024). Assessment from reciprocity: a space for co-construction in training of the physical education teachers. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 19(61), 2104. https://doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v19i61.2104