Academic Performance and Competence Perception in Physical Education Final Year Projects

Esther Magaña-Salamanca, Víctor M. López-Pastor, Juan Carlos Manrique-Arribas

Academic Performance and Competence Perception in Physical Education Final Year Projects

Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, vol. 18, no. 55, 2023

Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia

Esther Magaña-Salamanca * esther.magana@uva.es

University of Valladolid, Spain

Víctor M. López-Pastor

University of Valladolid, Spain

Juan Carlos Manrique-Arribas

University of Valladolid, Spain

Received: 15 july 2022

Accepted: 02 september 2022

Abstract:

The present study aims to examine to what extent the global academic performance achieved in the Degree/Master's Degree determines the level of competencies acquired through the final year project (TFG for Degrees and TFM for Master's Degrees) in Physical Education pre-service teacher education (PSTE-PE). The study was conducted based on the replies to a questionnaire that was built ad-hoc on the basis of studies regarding competency perception scales. The sample consisted of 325 participants from 34 Spanish universities: 186 students and 139 graduates. In this study, a comparative correlational design was used, where one variable referred to the perception of (cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific teaching) competencies acquired by PSTE-PE students and graduates during their TFG/TFM, and the other one was related to the global academic performance shown by those students and graduates during their Degree/Master's Degree studies. The results confirmed a significant relationship between the students and graduates' global academic performance in PSTE-PE and the competencies examined (cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific teaching competencies): the higher the academic performance, the better the competency perception.

Keywords: pre-service teacher education, Final Degree Project, Final Master's Degree Project, competence self-perception, academic performance.

Resumen:

El presente estudio tiene como finalidad analizar en qué medida el rendimiento académico global mostrado en el grado/máster determina el grado/nivel de competencias adquiridas en los Trabajos de Fin de Título (Grado –TFG- y Máster –TFM-) en la formación inicial del profesorado (FIP) de Educación Física (EF). Para la realización del estudio se han tenido en cuenta las respuestas obtenidas a partir de un cuestionario elaborado ad hoc, basado en estudios sobre escalas de percepción de competencias. Para ello se ha contado con un total de 325 participantes de 34 universidades españolas, 186 estudiantes y 139 egresados. Se ha llevado a cabo un diseño comparativo-correlacional en el que se vinculan variables de percepción de competencias adquiridas en los TFG/TFM (transversales, docentes genéricas y docentes específicas de EF) por parte de estudiantes y egresados de FIP- EF y la variable relacionada con el rendimiento académico global mostrado por dichos estudiantes y egresados a lo largo del Grado/Máster. Los resultados comprueban la relación significativa entre el rendimiento académico global en la FIP-EF del alumnado y egresados y las competencias estudiadas (transversales, docentes genéricas y docentes específicas de EF), descubriendo que cuanto mayor es el rendimiento académico mayor es su percepción de competencia.

Palabras clave: formación inicial, Trabajo Fin de Grado, Trabajo Fin de Máster, autopercepción competencial, rendimiento académico.

Introduction

The Spanish educational system has undergone constant changes, moving from a goal-based system promoted by the 1970 General Education Act (Ley General de Educación), which aimed at assessing the level of achievement through the measurement of certain learning outcomes, to the current system, especially since the 1990 General Organic Act for the Educational System (Ley Orgánica General del Sistema Educativo, LOGSE), which proposed a competence-based approach. The aim of this approach was to help students learn how to behave in a self-conscious and self-directed way within our model of society, in order to become more competent and qualified, and to be able to continuously update their skills and knowledge (Camoiras et al., 2018; Chocarro et al., 2007).

In university education, and more specifically in Physical Education pre-service teacher education (PSTE-PE), final year projects (TFG for the Degree and TFM for the Master's Degree) are used to demonstrate the knowledge and, in this case, the competencies acquired during the learning process. In High Education these competencies are classified as follows: (1) cross-curricular (formative and professional profile, beyond the curriculum), (2) general (common to all professions, we will focus on teaching), and (3) specific (relative to a specific area, PE in this case) (Salcines et al., 2018).

Besides, apart from measuring the level of achievement of the competencies required in the degrees, it is necessary to correlate it with the global academic performance of university students. Consequently, it can be understood that the self-perception of the competencies shown in the final year projects, which are supposed to include a large part of the established competencies, matches the final score obtained and the new content learned. A research gap in this scientific field has been detected, which will try to be covered by means of this study. Furthermore, we will take the opportunity to question whether these final year projects really reflect all the degree competencies acquired during the learning process or only a part of them.

Academic Performance

One indicator of the teaching-learning process success level that has received special attention is academic performance. It is assessed through a score, usually given by the teacher (Oyarzún et al., 2012). According to Beltrán (1998), academic performance (AP) refers to a quantitative-qualitative expression that measures the students' achievements and knowledge in every stage of the educational process. By contrast, González and González (2014) understood it as the average score obtained at the end of the school year in a specific subject matter. Authors like Jiménez (2000) and Cominetti and Ruiz (1997) claim that it is the knowledge in one area or subject shown through an assessment process that is seamlessly applied considering the factors that affect the education action, such as educational context, teaching quality or teacher's performance.

If we focus on university education, Gutiérrez-Monsalve et al. (2021) stated that academic performance is a complex concept that refers to the value given to the learning outcomes shown by students in a specific subject area, compared to the knowledge level expected from their peers. Upon this statement, the question arises whether it is necessary to establish comparisons with other students in order to determine performance. Oliva et al. (2011) understood AP as the final quantitative score obtained in every subject. Initially, it could be classified as success or failure (passed or not passed/failed), depending on the cut-off points set by the corresponding body to decide regarding its achievement or not. Nevertheless, it is advisable to take into account the different levels within 'passed' (in Spanish, from worst to best: aprobado [50-69/100], notable [70-89/100], sobresaliente [90-100/100], matrícula de honor [academic distinction awarded to the best 2-3 students with sobresaliente]). Theoretically, AP represents the relationship between what a student learns and what is achieved within the teaching-learning process, and it is eventually assessed through a score. Given the difficulty to match performance to learning outcomes, Rodríguez et al. (2004) distinguished two categories: immediate AP (referring to scores) and mediate AP (referring to the acquired learning and personal achievements).

Thus, general AP is considered to be an essential quality indicator in all educational stages. This study will focus on pre-service teacher education (Montero Rojas & Villalobos Palma, 2007; Díaz et al., 2002). The factors associated with university students' AP, which affect the learning outcomes and scores to a greater or lesser extent, can be either internal or external to the individual (Huy et al., 2005). Those with the strongest influence include academic, pedagogical, teaching (teaching strategies, assessment methods, teaching materials and resources), institutional (number of courses, academic progress, scholarships granted), socio-demographic (sex, age, family context, employment status, previous academic performance) and psychosocial factors (self-control, self-efficacy, self-concept, anxiety, motivation and intellectual ability) (Gutiérrez-Monsalve et al., 2021). As it can be noted, the psychological component shown by a student during the teaching-learning process will be significantly related to their cognitive development and their academic performance (Navarro, 2003) and, consequently, to their self-perceived competencies. Goleman (1996) stated that a student's PA depends on the most essential knowledge of all: learning to learn. The author highlighted self-control as one of the aspects to be re-educated in students, as well as confidence, curiosity, intentionality, and communication and cooperation skills. Yuste (2016) confirmed the above and added that university students with a positive perceived academic self-efficacy are associated with successful academic performance.

Furthermore, there are studies like the one by Lamas (2015) that underlined the important role played by a student's personality and motivation in achieving a specific performance level. Hidalgo-Fuentes et al. (2021) considered that responsibility was another determining factor in AP, as well as a powerful and significant predictor of this variable. Actually, according to Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham (2005), the more responsible students presented greater motivation to achieve optimal academic performance. By contrast, it is common that procrastinators do not show good academic performance, since they do not meet the essential criteria to get good marks, such as having systematic study habits or being able to meet deadlines (Balkis & Erdinç, 2017).

Consequently, there is a strong connection between performance and competencies, since they have multiple common aspects that affect each other, such as responsibility, adaptability, creativity or cooperation. Additionally, Fernández (2018) suggested that academic performance and outcomes must be used as feedback to continuously improve competency achievement.

Competency Self-Perception

Competencies refer to the skills and abilities that are necessary to adequately perform in different contexts (Callejas, 2015). Nowadays, the concept has gained complexity and acquired several meanings, since it is not only a set of knowledge, abilities and skills that are applied to problem-solving associated with a specific professional profile, but it also has psychological and social connotations (Romero, 2009).

Official university degrees must include the general and specific competencies that students need to acquire during their studies (Ayza, 2010). In particular, the Education Degrees programmes address the basic competencies related to general teaching knowledge and skills. Besides, specific competencies are oriented to the acquisition of teaching knowledge and skills related to the epistemological knowledge and contents of certain areas, like PE in this case (Cano, 2009). In short, during the training process of future teachers, students must be provided with those competencies that are necessary to become good professionals and to ensure educational quality and significance through the subject taught (Romero, 2004).

Higher Education faces the challenge of adequately preparing students for a society based on knowledge and employment possibilities. Therefore, teachers must re-think their work as teachers and adapt to these changes to provide their students with quality learning (Martínez & González, 2019). This leads to the competency approach championed by the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and related to teaching intervention (planning, implementation and assessment). Zabala and Arnáu (2008) defined teaching competencies as the abilities or skills to perform tasks, or the best way to effectively handle different situations in various contexts, where it is necessary to apply attitudes, skills and knowledge at the same time. Therefore, teaching competencies surround how we should be (competent teachers) and what we should do (teach competencies to our students) to help students face increasing and evolving challenges.

In fact, competency assessment is a critical step to determine their level of achievement and the influence they have on each other, in order to assess the success rate and performance in PSTE. Previous studies, like those conducted by Boyle and Petriwskyj (2014) and Trede and McEwen (2015) revealed the importance of consistency between the learnings acquired by university students and the professional practice they will perform in their future careers. Therefore, teaching competencies must relate theoretical training to the applicability of what was learned (Castillejo-Olán et al., 2019). As stated by Sarceda-Gorgoso and Rodicio-García (2018), the professional competencies that future graduates need to develop must align with what they will be required as experts in their fields. Thus, it is necessary to design an assessment system that includes all the sensitive information to determine the acquisition level of the competencies planned.

Formative assessment has proven to improve the teaching-learning process outcomes, student motivation and teaching competencies in pre-service teacher education (Hortigüela et al., 2015; Martos et al., 2014). This is because students' engagement and decision-making in the assessment processes enhance the acquisition of general and specific competencies during teacher education and, consequently, improve their competency self-perception (Castejón et al. 2011; Hernando, 2017). Multiple studies have previously addressed competency analysis, assessment and self-perception in PSTE-PE students. The studies by Asún et al. (2020) and Palacios-Picos et al. (2019) proposed a questionnaire for competency assessment, which is very useful to assess and improve professional competencies in the different PSTE subjects. Besides, the studies by Cañadas et al. (2019), Cañadas et al. (2021), Gallardo-Fuentes et al. (2020), Hamodi-Galán et al. (2018) and Romero et al. (2017) emphasised the positive relationship between formative assessment and perceived competency acquisition. Moreover, Molina et al. (2020) added that these assessment systems also improve the student's academic performance. The results revealed the importance of formative assessment and feedback in PSTE for competency improvement in PE and, consequently, they must contribute to the development of the general and specific teaching competencies students will put into practice in their future careers. Nevertheless, research that associates these competencies with global academic performance is scarce.

Therefore, the main hypotheses of the present study are: global academic performance in PSTE-PE affects (1) the perception of cross-curricular competencies shown in the TFG/TFM, (2) the perception of general teaching competencies shown in the TFG/TFM, and (3) the perception of PE-specific competencies shown in the TFG/TFM.

Method

In this study, a comparative correlational design was used, where one variable was the perception of (cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific teaching) competencies shown by PSTE-PE students and graduates in their TFG/TFM, and the other one was the global academic performance shown by these students and graduates during their Degree/Master's Degree studies.

Participants

The participants were selected through non-probabilistic sampling, based on the Spanish universities that volunteered to participate in the study. The sample consisted of 325 participants from 34 Spanish universities: 186 students and 139 graduates. All graduates had completed their degree within the previous three and five years. In the sample, there were 103 students and 53 graduates with a Degree in Primary Education, with specialisation in Physical Education, and 83 students and 86 graduates with a Master's Degree in Secondary Teacher Education with specialisation in Physical Education.

Instrument

A questionnaire called 'Questionnaire for Competency Assessment in TFGs/TFMs of Physical Education Teacher Education Studies' was used to collect the information. It was designed ad hoc for students and graduates who have completed a TFG and/or TFM related to PSTE-PE. Therefore, two versions were created, one for each group.

The questionnaire was built following several phases. The first one was the content validation by experts and graduates. To do so, a first extended version was used, created from various studies on competency perception scales (Salcines-Talledo et al., 2018; Palacios-Picos et al., 2019). These authors are members of the research team of the network for formative and shared assessment in education (Red de Evaluación Formativa y Compartida en Educación, REFYCE). For this study, many competencies were amended to make them reflect better those that are specifically applied in the TFG/TFM. Then, the questionnaire was administered to a sample of 14 experts and 94 graduates in order to polish the scale by removing those competencies that were less relevant to write these final year projects. Reliability values were high in all cases (α Total p = .931; α Cross-Curricular Competencies p = .786; α General Teaching Competencies p = .846; α Physical Education-Specific Competencies p = .931).

After the first pilot phase, the questionnaire was administered to both groups through Google Forms app between June and July 2021. This questionnaire consisted of:

-

(1) One section regarding socio-demographic data (6 items).

-

(2) One scale to measure the perceived competency development through the TFG/TFM, built based on the Scale of cross-curricular and professional competency self-perception by Higher Education students, validated by Salcines et al. (2018) and the Questionnaire on PE teaching competency perception, validated by Palacios-Picos et al. (2019). The final questionnaire was composed of 39 items divided into three categories: (a) cross-curricular competencies (12 items), (b) general teaching competencies (10 items) and (c) PE-specific competencies (17 items). The items were based on the statement 'Determine to what extent the TFG/TFM you are working on (students)/you delivered (graduates) has helped you develop (competency)' and had to be answered on a five-point Likert-type scale (not at all, very little, somewhat, quite a lot, a lot). An example item per type of competence would be: cross-curricular: 'to think in a critical and reflexive manner'; general teaching: 'to design learning situations'; and PE-specific: 'to be able to use the game as a teaching resource and teaching content'.

-

(3) One section regarding TFG/TFM context aspects and academic performance during the Degree/Master's Degree (average mark), with 16 items for students and 17 for graduates. One additional item was included for graduates in order to determine whether they had completed their TFG/TFM during the lockdown period due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this study will focus on the perception of cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific competencies, as well as academic performance.

Procedure

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS v.21 software for Windows. Firstly, an exploratory analysis was conducted through Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk normality tests, which yielded a significance level of p = .000, revealing that the dataset (cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific competencies, and global academic performance) did not follow a normal distribution. Subsequently, given the absence of normality, the correlation between the means of both variables (competence perception and academic performance) was examined through a non-parametric test for independent samples: Kruskal-Wallis H test. This test was conducted for students and graduates together, in order to work with a larger sample.

The results have been organised in several parts, based on the questionnaire's structure: whether the students and graduates' global performance affected (1) the self-perception of cross-curricular competencies, (2) the self-perception of general teaching competencies, especially those a teacher must have a good command of, and (3) the self-perception of PE-specific competencies, exclusive of this area. The statistical analysis started with the mean comparisons, with the purpose of statistically verifying the differences and confirming the absence of normality. Tables 1, 2 and 3 contain the mean for each group, obtained as the average score on the questionnaire Likert scale (1-5).

After having compared the means and confirmed the absence of normality, the ANOVA was discarded. Instead, a Kruskal- Wallis test for independent samples was conducted. This is a non-parametric test that verifies the existence of statistically significant differences between two or more groups of an independent variable (global academic performance in PE pre-service teacher education) in a dependent variable (the three categories of competencies acquired during the TFG/TFM).

Results

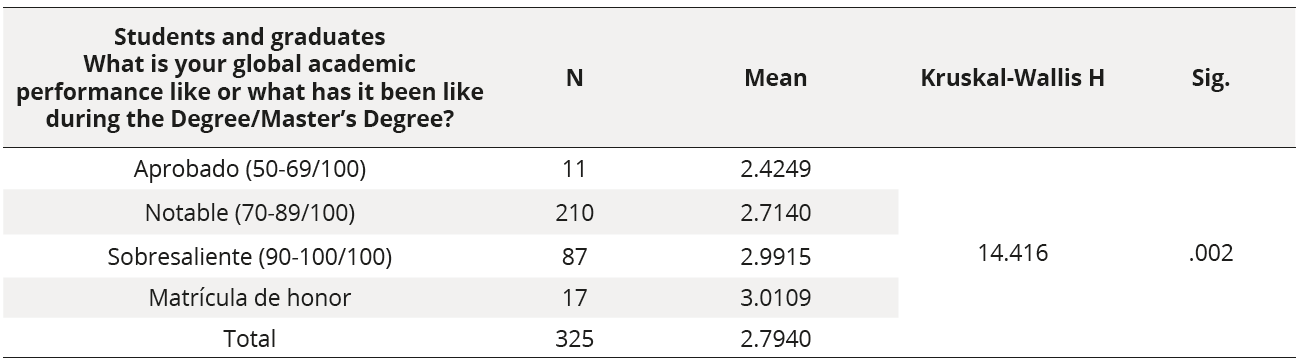

The first study hypothesis referred to the effect of global academic performance during PSTE-PE on the perception of the cross-curricular competencies shown in the TFG/TFM, and the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed significant differences between the variables (. = .002) (Table 1).

Consequently, we can say there were significant differences between groups. Thus, the higher the global academic performance in the Degree/Master's Degree, the higher the perception of cross-curricular competencies acquired during the final year projects. That means performance did affect the self-perception of cross-curricular competencies.

Comparative statistical analysis of performance and cross-curricular competencies

KeyN=number of participants; Sig.=significance

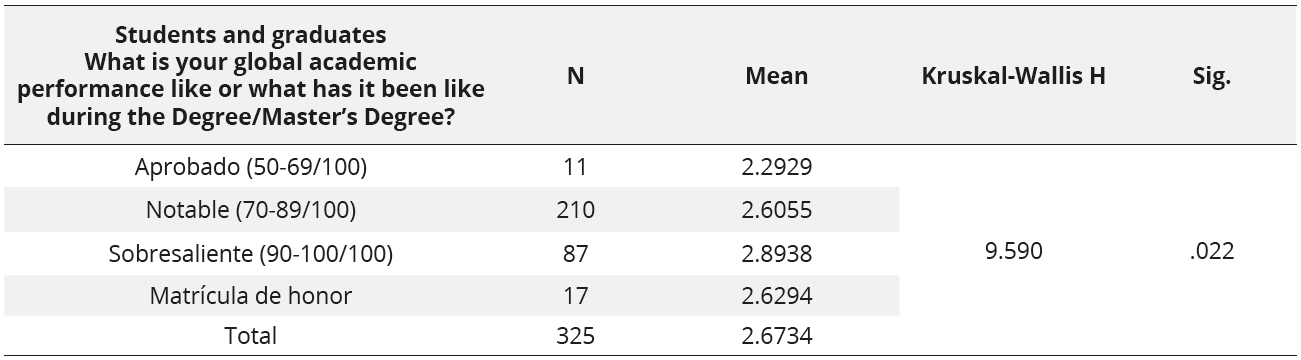

The second hypothesis was related to the effect of global academic performance during PSTE-PE on the perception of the general teaching competencies shown in the TFG/TFM. Table 2 displays the significance level obtained, p = .022 (Sig < .05).

Therefore, in this case, significant differences were also observed between groups. Thus, the higher the PSTE-PE students and graduates' general academic performance, the higher their perception of general teaching competencies, except for the group with a mark of 'Matrícula de honor', which presented a lower mean than the group with 'Sobresaliente'. Despite this, we can highlight that global performance did affect the self-perception of general teaching competencies acquired during the TFG/TFM.

Comparative statistical analysis of performance and general teaching competencies

KeyN=number of participants; Sig.=significance

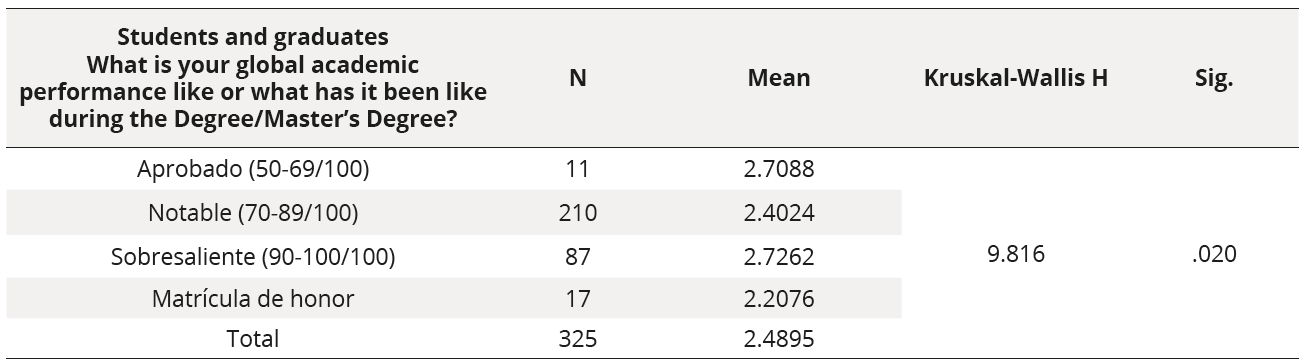

The third hypothesis referred to the effect of global academic performance during PSTE-PE on the perception of the PE-specific competencies shown in the TFG/TFM. Table 3 shows the results, which were again significant in the different groups (p = .020; Sig < .05). Therefore, we can say that performance also seemed to affect the self-perception of PE-specific teaching competencies.

Despite this, differences can be observed among groups regarding the above variables, which did not follow a clear pattern. In this case, the group with a mark of 'Sobresaliente' presented the best perception, followed by the groups with 'Aprobado' and 'Notable'. By contrast, the worst perception corresponded to the group with 'Matrícula de honor'.

Comparative statistical analysis of performance and PE-specific competencies

KeyN=number of participants; Sig.=significance

In short, the global academic performance shown by students and graduates during PSTE-PE seemed to generally affect their self-perception of the three types of competencies acquired during the final year project: (1) cross-curricular, (2) general teaching and (3) PE-specific teaching competencies. Nonetheless, it must be borne in mind that the means of competency types 2 and 3 followed different orders.

Discussion

In this section, the question that has guided this research will be answered: how does global academic performance during PSTE-PE influence the perception of the teaching competencies acquired during the final year project (TFG/TFM)? The results proved that this relationship was significant in students and graduates for the three types of competencies examined (cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific teaching competencies). These results are in keeping with the findings by Gallardo et al. (2018), López- Varas (2015), Omar (2004) and Peiffer et al. (2020), and it is noteworthy that students felt more competent as their academic performance increased.

In this regard, Castillo et al. (2003) and Vargas (2007) highlighted those students with a high perception of their own competency acquisition usually presented higher academic performance. Gargallo et al. (2009) also brought to light the need for students to have a good perception of their competencies in order to achieve better academic performance.

This research revealed a strong relationship between the perception of cross-curricular competencies and academic performance. This may be because these competencies are common to all professional profiles and they are essential to respond to social and work demands (Núñez-Flores et al., 2021). Likewise, Cabrerizo et al. (2008) considered that these competencies may be seen as different aspects of the general training for Higher Education students.

Previous studies have provided results regarding the association between cross-curricular competency perception and performance. For example, Aguado et al. (2017) stated that cross-curricular competencies showed a significant relationship with academic performance, essentially based on the interest in quality, learning ability and responsibility. By contrast, Amor and Serrano (2018) and Clemente and Escribá (2013) considered that the most important cross-curricular competencies, which allowed students to achieve higher performance, were: teamwork, organisation and planning, and oral and written communication in their native language. Therefore, previous scientific literature suggested a relevant relationship between students and graduates' self-perception of these competencies and performance.

Likewise, it was confirmed that the perception of general teaching competencies was strongly associated with academic performance, with significant differences among marks. This can be observed in the studies by Gutiérrez et al. (2011), Hamodi (2018) and Quiroz and Franco (2019), who explained that the more positive the experiences and the better the academic outcomes, the better the perception of professional competencies, in this case related to teaching. Within this competency category, Cañadas et al. (2019) underlined the importance of teaching skills and pedagogical content knowledge. Based on the results of our study, it was confirmed that acquiring and perceiving these competencies during PSTE enables students to achieve better academic performance and could, therefore, have a positive influence on their future professional performance. Such interpretation can be linked with the studies by Hamodi et al. (2018) and Mas-Torelló and Olmos-Rueda (2016), which highlighted that general teaching competencies during PSTE were closely related to the interest in improving teaching practice and its professionalisation; that is, knowing what and how to teach, who you teach and what to teach for.

The studies by Gallardo and Carter (2016), Gallardo et al. (2018) and Tejada-Fernández, et al. (2017) pointed out that the internship can be essential to establish this type of relationship, as it strongly affects the perception of general teaching competencies, as well as the global academic performance, due to two potential reasons: (a) the final mark of the different internship courses are highly influenced by the students' teaching skills at the primary school; (b) the internship contains many credits and, therefore, has considerable influence on the whole degree performance. In this regard, Ojeda et al. (2019) stated that students enhance their education and improve their academic performance during their internship by experiencing real learning situations, through which they acquire and incorporate new professional competencies. This is a big strength, since it allows them to apply and transfer these teaching competencies to various contexts. Besides, the learnings from the last degree internship completed can also be applied to the final year project, as it happened in our study, by adopting a critical and thoughtful view that allows students to associate theory and practice, as stated by Delicado et al. (2018) in their research.

Significant differences between groups were also detected in the relationship between the perception of PE-specific teaching competencies and academic performance. Nevertheless, these differences did not follow a clear pattern, as it happened with the previous two variables. The groups which presented the best competency self-perception were those with 'Sobresaliente' and 'Aprobado', followed by those with 'Notable' and, finally, 'Matrícula de honor'. A potential explanation of such differences could be related to the small sample size of the groups with 'Aprobado' and 'Matrícula de honor', which may have caused deviations in the measurements. That said, the following explanatory hypotheses are proposed:

-

a) A considerable percentage of students had previously completed the vocational training for physical activity and sports recreation (Técnico Superior en Actividades Físicas y Animación Deportiva, TAFAD) or had worked as sports instructors, either before or during the degree, so they perceived themselves as more competent, but they usually had lower academic performance. This may be because, as stated by Ruiz-Artola (2007), TAFAD builds professionals with a qualification that is specific to the physical activity industry and directly related to their future working activities.

-

b) The perception of PE-specific teaching competencies may be influenced to a greater extent by other non-controlled variables, such as previous experience as an athlete, previous or concomitant experience as a sports instructor, or sports education received out of the degree (sports instructor or trainer, specific professional training, etc.). With regard to this hypothesis, Clemente and Escribá (2013) pointed out that the perception of acquired competencies in students who have previously worked or are currently working in the sports industry is better than in those who are only studying.

PSTE-PE students and graduates showed significant differences in the relationships between their self-perception of PE-specific competencies during their TFG/TFM and global performance. It was noteworthy that the pattern detected was different from the other two types of competencies, which may be affected by other non-controlled variables such as previous training and/or experience as sports professionals and/or previous experience as athletes. Moreover, some graduates may have a different competency self-perception after their first contact with real teaching, when they have to face the various difficulties involved in real professional activity.

In short, the findings of our study showed a clear general relationship between competency self-perception during the TFG/TFM and global performance in PSTE-PE students and graduates. In this regard, Gallardo et al. (2018) showed in their results that the self-perception of professional competencies acquired in PSTE through a formative and shared assessment method yielded high levels of the three competency categories examined: cross-curricular, general teaching and PE-specific teaching competencies. However, it was also found that students and graduates presented higher self-perception of the cross-curricular competencies acquired than the PE-specific and general teaching competencies, which is in line with the results by Hamodi (2018). By contrast, the studies by Gutiérrez et al. (2018) and Romero et al. (2017) addressing the three types of competencies in PSTE obtained average values for all of them (between two and three on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 4).

Conclusions

The global performance shown by students and graduates during PSTE-PE seemed to significantly affect their self-perception of the three types of competencies acquired during the final year project: (1) cross-curricular, (2) general teaching and (3) PE-specific teaching competencies; however, the pattern was different in the latter. These differences in the perception of PE-specific teaching competencies may be influenced by non-controlled variables, such as previous training and/or experience related to sports and/or physical activity.

To conclude, as regards the main study hypothesis, it was confirmed that global academic performance during PSTE-PE determined to a great extent the perception of the competencies acquired during the final year project, both in students and graduates. Therefore, performance seemed to affect the perception of competencies of the three categories during the final year projects, despite the slight differences found in the last type.

This study provides results and an initial approach to a research field that has not been deeply explored yet and offers a view of the direct relationship between the perception of acquired competencies and academic performance. Therefore, it may be useful to all PSTE-PE teachers, as well as to researchers working in this area.

The major limitations of the present study are related to sample size, which affects the result generalisation, and to the potential influence of two non-controlled variables (previous or concomitant training and/or experience as sports instructors and previous experience as athletes). Consequently, it is deemed necessary to conduct more exhaustive studies with larger samples and try to collect contextual data on the two variables mentioned. It would also be interesting to apply a mixed design, with a more qualitative approach that allows for a better interpretation of the quantitative results. A future research line could compare the PE students and graduates' competency perception with the teachers' perception.

Funding

This research is part of R+D+i project RTI2018-093292-B-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and ERDF 'A way to make Europe'. Approved by the research ethics committee of Aragón (Comité Ético de Investigación de la Comunidad de Aragón, CEICA), C.P.-C.I.PI21/377.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andrés Palacios for his contribution to improving the manuscript.

Bibliography

Aguado, D., González, A., Antúnez, M., & de Dios, T. (2017). Evaluación de competencias transversales en universitarios. Propiedades psicométricas iniciales del cuestionario de competencias transversales. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 15(2), 129-152. DOI:10.15366/REICE2017.15.2.007

Amor, M. I., & Serrano, R. (2018). Análisis y Evaluación de las Competencias Genéricas en la Formación Inicial del Profesorado. Estudios Pedagógicos, 44(2), 9-19. Recuperado de http://revistas.uach.cl/index.php/estped/article/view/4137

Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2017). Gender differences in the relationship between academic procrastination, satisfaction with academic life and academic performance. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 15(1), 105-125. https://doi.org/10.14204/ejrep.41.16042

Boyle, T., & Petriwskyj, A. (2014). Transitions to School: Reframing Professional Relationships. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 34(4), 392-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2014.953042

Callejas, J. S. (2015). El modelo y enfoque de formación por competencias en la Educación Superior: apuntes sobre sus fortalezas y debilidades. Revista Academia y virtualidad, 8(2), 5. DOI:10.18359/ravi.1420

Camoiras, Z., Benito, J. L, & Varela, C. (2018). La motivación de los alumnos en la Educación Superior: evaluación de una experiencia docente. En A. Villa. (Ed.), Tendencias actuales de las transformaciones de las universidades en una nueva sociedad digital (pp. 631-374), Foro Internacional de Innovación Universitaria. Recuperado de http://www.foroinnovacionuniversitaria.net/tendencias-actuales/

Cañadas, L., Santos-Pastor, M. L., & Castejón, F. J. (2019). Competencias docentes en la formación inicial del profesorado de educación física. Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deportes y Recreación, 35, 284-288.

Cañadas, L., Santos-Pastor, M. L. & Ruiz, P. (2021). Percepción del impacto de la evaluación formativa en las competencias profesionales durante la formación inicial del profesorado. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 23(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2021.23.e07.2982

Castejón, F.J., López-Pastor, V.M., Julián, J.A., & Zaragoza, J. (2011). Evaluación formativa y rendimiento académico en la formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Física. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 11(42) 328-346. http://dx.doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2015.58.004

Castillejo-Olán, R., Álvarez-Vera, E. K., & Granados-Romero, J. F. (2019). Evaluación y autopercepción de competencias docentes para la gestión de la clase en educación física. Arrancada, 19(35), 108-117. Recuperado de https://revistarrancada.cujae.edu.cu/index.php/arrancada/article/view/301/216

Castillo, I., Balaguer, I., & Duda, J. L. (2003). Las teorías personales sobre el logro académico y su relación con la alienación escolar. Psicothema, 15(1), 75-81.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2005). Personality and intellectual competence. London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chocarro, E., González-Torres, M.C., & Sobrino, J. (2007). Nuevas orientaciones en la formación profesorado para una enseñanza centrada en la promoción del aprendizaje autorregulado de los alumnos. Estudios Sobre Educación, 12, 81-98.

Clemente, J.S., & Escribá, C. (2013). Análisis de la percepción de las competencias genéricas adquiridas en la Universidad. Revista de Educación, (362), 535-561.DOI: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2013-362-241.

Delicado, M., Trujillo, J., & García, L. (2018). Valoración sobre la formación en la mención de Educación Física, por parte del alumnado de Grado en Educación Primaria. Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física Deportes y Recreación, 34, 194- 199. http://dx.doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i34.59314

Fernández, S. (2018). Rendimiento académico en educación superior: desafíos para el docente y compromiso del estudiante. Revista Científica de la UCSA, 5(3), 55-63. https://doi.org/10.18004/ucsa/2409-8752/2018.005(03)055-063

Gallardo, F., & Carter, B. (2016). La evaluación formativa y compartida durante el prácticum en la formación inicial del profesorado: Análisis de un caso en Chile. Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física Deportes y Recreación, 29, 258-263. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3457/345743464048.pdf

Gallardo-Fuentes, F., López-Pastor, V. & Carter-Thuillier, B. (2020). Ventajas e Inconvenientes de la Evaluación Formativa, y su Influencia en la Autopercepción de Competencias en alumnado de Formación Inicial del Profesorado en Educación Física. Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 38, 417-424. Recuperado de https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/retos/article/view/75540

Goleman, D. (1996). Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books Psychology.

Gutiérrez, C., Hortigüela, D., Peral, Z., & Pérez-Pueyo, A. (2018). Percepciones de alumnos del Grado en Maestro en Educación Primaria con Mención en Educación Física sobre la Adquisición de Competencias. Estudios pedagógicos, 44(2), 223-239. DOI: 10.4067/s0718-07052018000200223

Gutiérrez-García, C., Pérez-Pueyo, Á., Pérez-Gutierrez, M., & Palacios-Picos, A. (2011). Percepciones de profesores y alumnos sobre la enseñanza, evaluación y desarrollo de competencias en estudios universitarios de formación del profesorado. Cultura y Educación, 23(4), 499-514. https://doi.org/10.1174/113564011798392451

Gutiérrez-Monsalve, J. A., Garzón, J., & Segura-Cardona, A. M. (2021). Factores asociados al rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Formación universitaria, 14(1), 13-24. DOI:10.4067/S0718-50062021000100013

Hamodi, C., Moreno, J. A., & Barba, R. (2018). Medios de evaluación y desarrollo de competencias en Educación Superior en estudiantes de Educación Física. Revista de Estudios Pedagógicos, 44(2), 241-257. DOI: 10.4067/S0718-07052018000200241

Hernando, A. (2017). Autopercepción de competencias adquiridas en la formación inicial del maestro de primaria. Revista Infancia, Educación Y Aprendizaje, 3(2), 729–734. https://doi.org/10.22370/ieya.2017.3.2.809

Hidalgo-Fuentes, S. H., Álvarez, I. M., & Baeza, M. J. S. (2021). Rendimiento académico en universitarios españoles: el papel de la personalidad y la procrastinación académica. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 14(1), 5. DOI:10.32457/EJEP.V14I1.1533

Hortigüela, D., Pérez-Pueyo, A., & López-Pastor, V.M. (2015). Implicación y regulación del trabajo del alumnado en los sistemas de evaluación formativa en educación superior. Relieve. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 21(1), 1-5. DOI: 10.7203/relieve.21.1.5171

Huy, L., Casillas, A., Robbins, S., & Langluy, R. (2005) Motivational and skills, social, and self- management of college outcomes: Constructing the student readiness inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(3), 482-508.

Lamas, H. A. (2015). Sobre el rendimiento escolar. Propósitos y representaciones, 3(1), 313-386. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2015.v3n1.74

López-Varas, F. (2015). Relaciones entre competencias, inteligencia y rendimiento académico en alumnos de Grado en Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte (Tesis doctoral, Universidad Europea de Madrid). Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/11268/4359

Martínez, P., & González, N. (2019). El dominio de competencias transversales en Educación Superior en diferentes contextos formativos. Educação e Pesquisa, 45, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634201945188436

Martos, D., Torrent, G., Durbá, V., Saíz, L., & Tamarit, E. (2014). El desarrollo de la autonomía y la responsabilidad en educación física: un estudio de caso colaborativo en secundaria. Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 26, 3-8. DOI:10.47197/RETOS.V0I26.34386

Mas-Torelló, Ó., & Olmos-Rueda, P. (2016). El profesor universitario en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior: la autopercepción de sus competencias docentes actuales y orientaciones para su formación pedagógica. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 21(69), 437-470.

Navarro, R. E. (2003). El rendimiento académico: concepto, investigación y desarrollo. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 1(2), 1-16. Recuperado de https://revistas.uam.es/reice/article/view/5354

Núñez-Flores, M. I., Hurtado-Espinosa, C. L., Vega-Calero, L. M., & Ramirez-Villacorta, Y. (2021). Perfil profesional por competencias y la empleabilidad en la formación docente de estudiantes universitarios. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales, 17(2). Recuperado de http://revistacientifica.uaa.edu.py/index.php/riics/article/view/1088

Oliva, F. C., López-Pastor, V. M., Clemente, J. J., & Casterad, J. Z. (2011). Evaluación formativa y rendimiento académico en la formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Física. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte/International Journal of Medicine and Science of Physical Activity and Sport, 11(42), 238-346. Recuperado de http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista42/artevaluacion163.htm

Omar, A. G. (2004). La evaluación del rendimiento académico según los criterios de los profesores y la autopercepción de los alumnos. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 34(2), 9-27.

Oyarzún, G., Estrada, C., Pino, E., & Oyarzún, M. (2012). Habilidades sociales y rendimiento académico: una mirada desde el género. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 15(2), 21-28. Recuperado de https://actacolombianapsicologia.ucatolica.edu.co/article/view/263

Palacios-Picos, A., López-Pastor, V., & Fraile-Aranda, A. (2019). Cuestionario de Percepción de Competencias docentes en Educación Física. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 19(75), 445-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2019.75.005

Rodríguez, S., Fita, E., & Torrado, M. (2004). El rendimiento académico en la transición secundaria-universidad. Revista de Educación, 334, 391-414.

Romero, C. (2004). Argumentos sobre la formación inicial de los docentes en educación física. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 8(1), p.1- 20.

Romero, C. (2009). Definición de módulos y competencias del maestro con mención en Educación Física. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte/International Journal of Medicine and Science of Physical Activity and Sport, 9(34), 179-200. Recuperado de http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista34/artcompetencias124.htm

Romero, M. R., Fraile, A., & Asún, S. (2017). Evaluación formativa de las competencias docentes en Educación Física. Infancia, Educación y Aprendizaje, 3(2), 518-523. Recuperado de http://revistas.uv.cl/index.php/IEYA/index

Ruiz-Artola, J. (2007). Análisis del perfil profesional del Técnico superior en animación de actividades físicas y deportivas a través de la formación en centros de trabajo (Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria). Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10553/3233

Salcines, I., González-Fernández, N., Ramírez-García, A., & Martínez-Mínguez, L. (2018). Validación de la Escala de Autopercepción de Competencias Transversales y Profesionales de Estudiantes de Educación Superior. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 22(3), 31-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v22i3.7989

Sarceda-Gorgoso, M. C., & Rodicio-García, M.L (2018). Escenarios formativos y competencias profesionales en la formación inicial del profesorado. Revista Complutense de Educación, 29(1), 147-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/RCED.52160

Tejada-Fernández, J., Carvalho-Dias, M. L., & Ruiz-Bueno, C. (2017). El prácticum en la formación de maestros: percepciones de los protagonistas. Magis. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 9(19), 91-114. DOI:10.11144/JAVERIANA.M9-19.PFMP

Trede, F., & McEwen, C. (2015). Early Workplace Learning Experiences: What Are the Pedagogical Possibilities beyond Retention and Employability? Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning, 69(1), 19-32. Recuperado de http://www.jstor.org/stable/43648771

Vargas, G. M. (2007). Factores asociados al rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios, una reflexión desde la calidad de la educación superior pública. Revista Educación, 31(1), 43-63. Recuperado de https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/440/44031103.pdf

Yuste, L. (2016). Creencias de autoeficacia docente en estudiantes de magisterio: análisis de su relación con variables de personalidad y bienestar psicológico y estudio del cambio (Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Valencia). Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12424/2192550

Zabala, A., & Arnau, L. (2008). Cómo aprender y enseñar competencias. México: Colofón-Graó.

Author notes

* Correspondence: Esther Magaña Salamanca, esther.magana@uva.es

Additional information

How to cite this article: Magaña-Salamanca, E., López-Pastor, V. M., & Manrique-Arribas, J. C. (2023). Academic Performance and Competence Perception in Physical Education Final Year Projects. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 18(55). https://doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v18i55.1950

ISSN: 1696-5043

Vol. 18

Num. 55

Año. 2023

Academic Performance and Competence Perception in Physical Education Final Year Projects

EstherVíctor M.Juan Carlos Magaña-SalamancaLópez-PastorManrique-Arribas

University of Valladolid,Spain