Origin, evolution and influence on the game of water polo rules

Pablo José Borges-Hernández, Francisco Manuel Argudo, Pablo García-Marín, Encarnación Ruiz-Lara

Origin, evolution and influence on the game of water polo rules

Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, vol. 17, no. 51, 2022

Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia

Pablo José Borges-Hernández

Universidad de La Laguna, España

Pablo García-Marín

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, España

Encarnación Ruiz-Lara

Universidad Católica de Murcia, España

Received: 04 October 2021

Accepted: 26 October 2021

Abstract: The aim of this study was to describe the origin and evolution of the different regulations in water polo that have existed throughout its almost one hundred and fifty years of history and their possible influence on the game dynamics. A content analysis of the texts published on paper by the Fédération Internationale de Natation was carried out, focusing on semantics, based on some key categories of this sport. The main conclusion is that many regulatory changes have been made over the years. However, there is no scientific evidence of their effects on the game dynamics.

Keywords: team sport, game action, rule modification.

Resumen: El objetivo de este estudio fue describir el origen y evolución de sus diferentes reglamentos a lo largo de sus casi ciento cincuenta años de historia y su influencia en la dinámica del juego. Se llevó a cabo un análisis de contenido de los textos publicados en papel por la Federación Internacional de Natación Amateur, centrándose en la semántica, a partir de algunas categorías clave de este deporte. Se concluye que han existido numerosos cambios normativos a lo largo de los años. Sin embargo, sigue sin existir evidencia científica de sus efectos en la dinámica del juego.

Palabras clave: deporte de equipo, acción de juego, modificaciones reglamentarias.

1. Introduction

The water polo is a young team sport product of Industrial Revolution (Lloret, 1994). In the beginning, the water polo was approximately a rugby like game played in the water, without any official rules established, in which everything was valid and everyone solved the situations on their own. It was played without goalpost or with the biggest goalpost ever seen, and the players had to deposit the ball behind the other team's bottom line. No shot could be taken, having to reach the target with the ball in their arms.

So why the name water polo? It is clear the first part of the word, water, where there is no clear agreement is on the second part, polo. According to Delahaye (1929, pp. 2-3), "the name water polo comes from polo aquatic and is reminiscent of a water game imagined in England around 200 years ago. In this game, the horses are replaced by empty barrels, in which the players are placed. Each one of them is equipped with a kind of stick that serves, at the same time, as a paddle to move and direct the device, and a stick to hit the ball”. Although there is no study on the relationship between horse polo and water polo, which derives in the current water polo, Vigarello (1988, pp. 46-48) points out: "the confirmation of countless imitations of gentlemen... like the confrontations of the oarsmen piloting the barrels-horses". From there, according to Lloret (1998, p. 22): "it is possible to think that, during the first half of the 19th century, the precursor game of water polo was this polo aquatic... for natural reasons because we understand that, in such practices, the players should often fall from the barrels to play the ball from the water, forcing them, in their evolution, to get rid of a heavy and impractical material. As they master the medium, they start a game in which they must swim with the ball into the liquid medium”.

Figure 1

Origin of Polo Aquatic according to Vigarello 1988 p 48

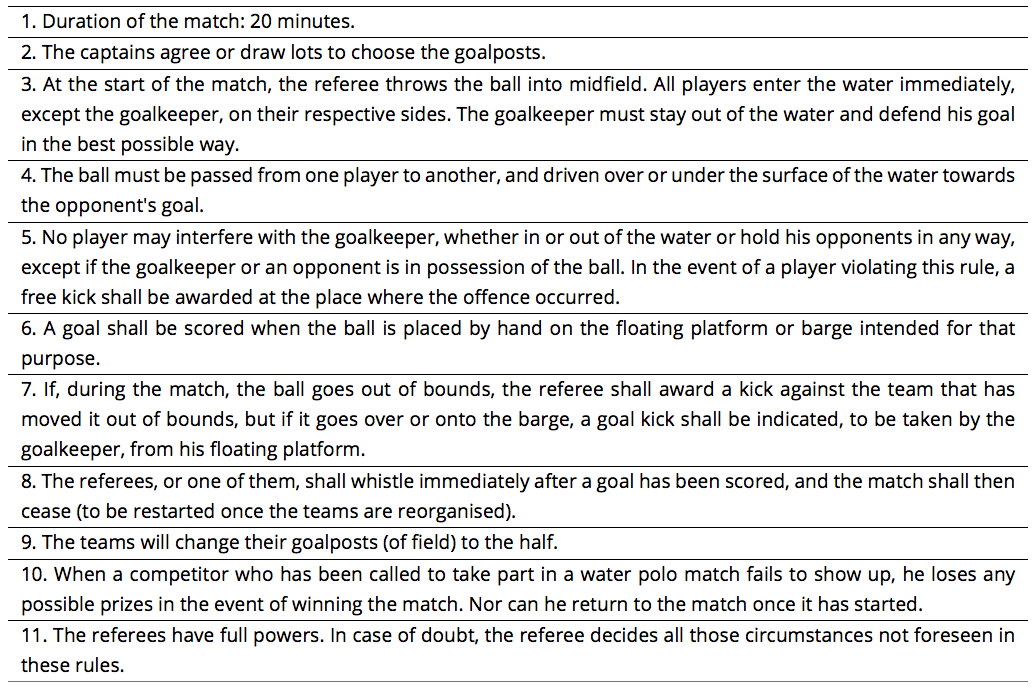

As with the name of polo, controversy arises in the development of the rules of the game. According to Delahaye (1929), it was Baxter who made the first rules of the sport. While Iguarán (1972) and Cuddon (1980), claim that Wilson, president of the Swimming Association, made the rules that gave birth to the sport (Table 1). The former gave the game some basic rules, but it was the latter who established the rules.

The first match took place in 1869 in London, without any regulation. As a result of this, rules were drawn up in 1870, which led to the names "Football in the water". At first, the number of players varied between 7 and 20, and the width of the goal was between 3 and 6 meters. These were demarcated by flags, and the goalkeeper could use a paddle or stick, about whose size there are some doubts. Finally, according to Rajki (1958, pp. 13-16), in 1876: “the Bournemouth Rowing Club played the first water polo match with regulated boundaries under the careful supervision of a referee and two goal judges. Each team consisted of seven players. There were no goals, and for the completion of the attack, the ball had to be placed in a raft, which meant the achievement of a goal or goal for the team that had deposited it. This first match was short lived as the fragile balls could not withstand the vigorous play and burst”. The first official regulations were drawn up in Glasgow in 1877, with goals appearing two years later and a series of matches between English and Scottish teams taking place three years later. Finally, in 1885, the English Swimming Association officially recognised water polo, providing it with a set of eleven articles (Table 1), according to Rajki (1958).

First water polo regulation of the English Swimming Association (Rajki 1958).

At the height of the expansion, according to Rajki (1958, pp. 14-15): "in 1890 water polo spread to the United States, where the rules were changed to convert it to indoor and small pools. These essential changes were not to allow a goal to be scored, but to allow a goal to be scored by touching a mark with the ball in your hand. In 1897 there was a restructuring of the rules unifying them with the European ones". In Germany, the first water polo match was played in Berlin in 1894, with the problem of not being able to play matches on a large scale, given that each club had its own rules. On 19 July 1908 the Fédération Internationale de Natation Amateur (FINA) was founded in London. In 1911, according to Rajki (1958, p. 15): "the FINA made it obligatory to revise the rules thoroughly, defining more precisely the boundaries of the field, the goals, the ball, the duration of the match, the characteristics of the game and the composition of the teams". Its aim was to unify regulations and that in every country there would be the same. Since then, FINA has been responsible for all the regulatory changes that have taken place in the almost 150-year history of water polo.

In relation to the studies that have analysed the regulatory changes that have been applied in water polo in recent years, the research of Donev & Aleksandrović (2008) and Madera et al. (2017) should be highlighted. Emphasising the results of Lozovina & Lozovina (2019b), who find no difference in their influence on the outcome of the game in terms of the number of possessions and estimate that only a third of the fouls are useful. Based on previous studies, it is proposed to regain the 4-meter line for penalty shots and to introduce a "bonus" when receiving more than 7 fouls per quarter. It also allows two-handed shots to be blocked, and adds that the midfield must be passed within 20 seconds, with a penalty if the ball returns to the goalkeeper (Hraste, Bebić, & Rudić, 2013; Lozovina & Lozovina, 2019a). Finally, mention should be made of the studies on the effects of the change of distance in the penalty shot (Argudo, Ruiz-Barquín, & Borges, 2016) and the use of time out by coaches (Ruiz-Lara, Borges-Hernández, Ruiz-Barquín, & Argudo, 2018). Although these have remained a mere description of existing regulations or very superficial analyses of the game, they are not interested in knowing how these changes have affected the development of the game, its actions and transfers to training (Ávila-Moreno et al., 2018).

For all these reasons and in view of the scarcity of scientific studies, the aim of this study was to describe the origin and evolution of the different regulations in water polo that have existed throughout its almost one hundred and fifty years of history and its possible influence on the game dynamics.

2. Materials of study and procedure

The present study is a content analysis (Bardin, 1986; Krippendorff, 1997), in particular an analysis of the regulatory modifications of water polo throughout its 150 years history. As it is a documentary material, it has been chosen to analyse what is written, but this does not prevent subsequent works from including other types of empirical analyses as the only study on the subject that is known, carried out by Madera et al. (2017). In this, they study the minutes of international matches according to the regulations in force in order to describe how these modifications have affected the game as a way of extending this study. Both, the literal part and the modifications observed in the game are considered the source of information for this study, although in our case, we have considered analysing only the text and comparing it with results of previous notational analysis of the sport in order to explain what changes have taken place in water polo.

For the analysis of the prevailing regulations, the official regulations published by FINA and the various authors who have studied this sport have been used (Madera et al, 2017; Lozovina & Lozovina, 2019a b). In this sense, and knowing that content analysis is not exclusively a qualitative technique (Flick, 2004), in this case, we will focus more on the semantic and pragmatic (Navarro & Díaz, 1995), and the relationships established between the content of the documents studied.

In order to carry out this analysis, a set of categories have been defined which correspond to the key aspects of the sport: materials, duration of the match, players and permitted actions and technical-tactical actions. This set of categories has been selected, to explain the development of the game as a whole and to be the classic analysis categories that have been used in the literature (Castejón et al., 2011). Each one of the documents has been analysed, applying the described categories, by all the members of this work individually, and later on a joint sharing, has been done in order to check the differences and similarities in the analysis. In those cases where wide differences appear between the researchers, this would be pointed out, discussing the suitability of the same.

3. Results

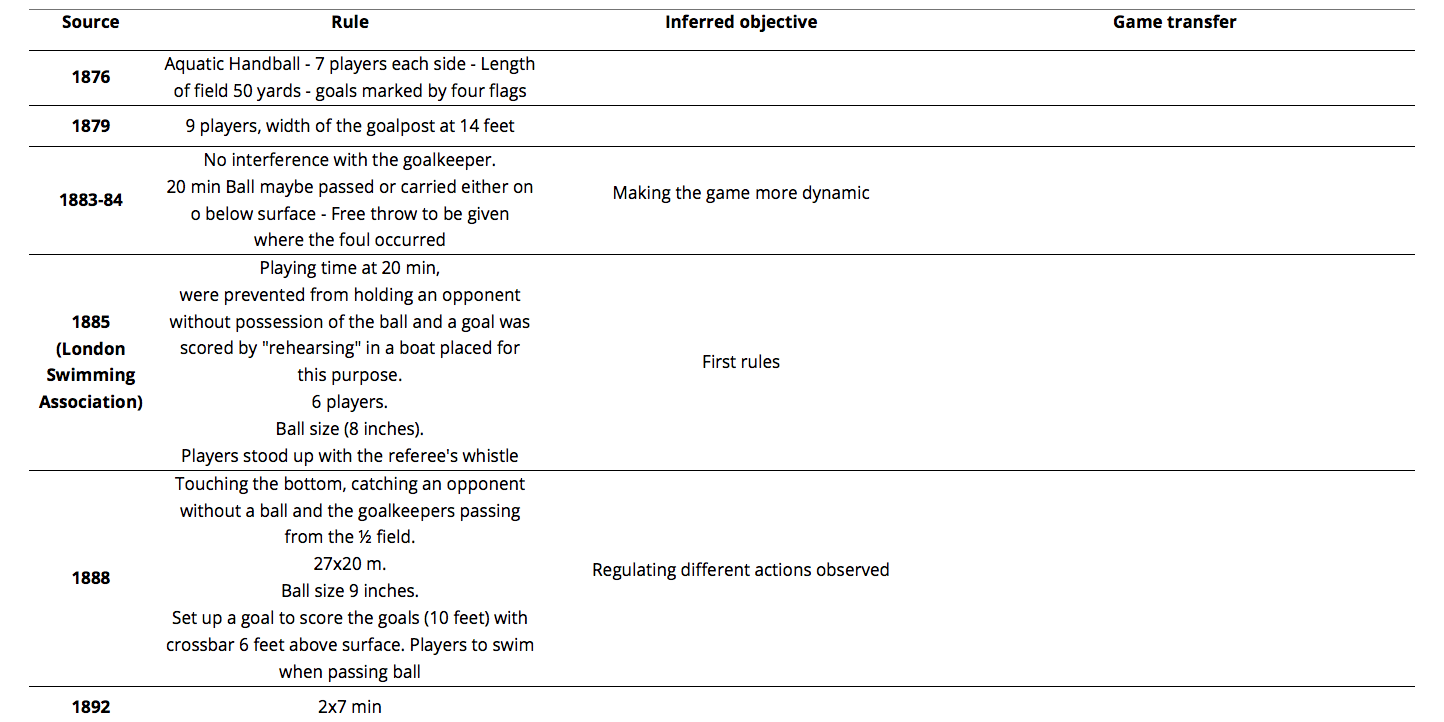

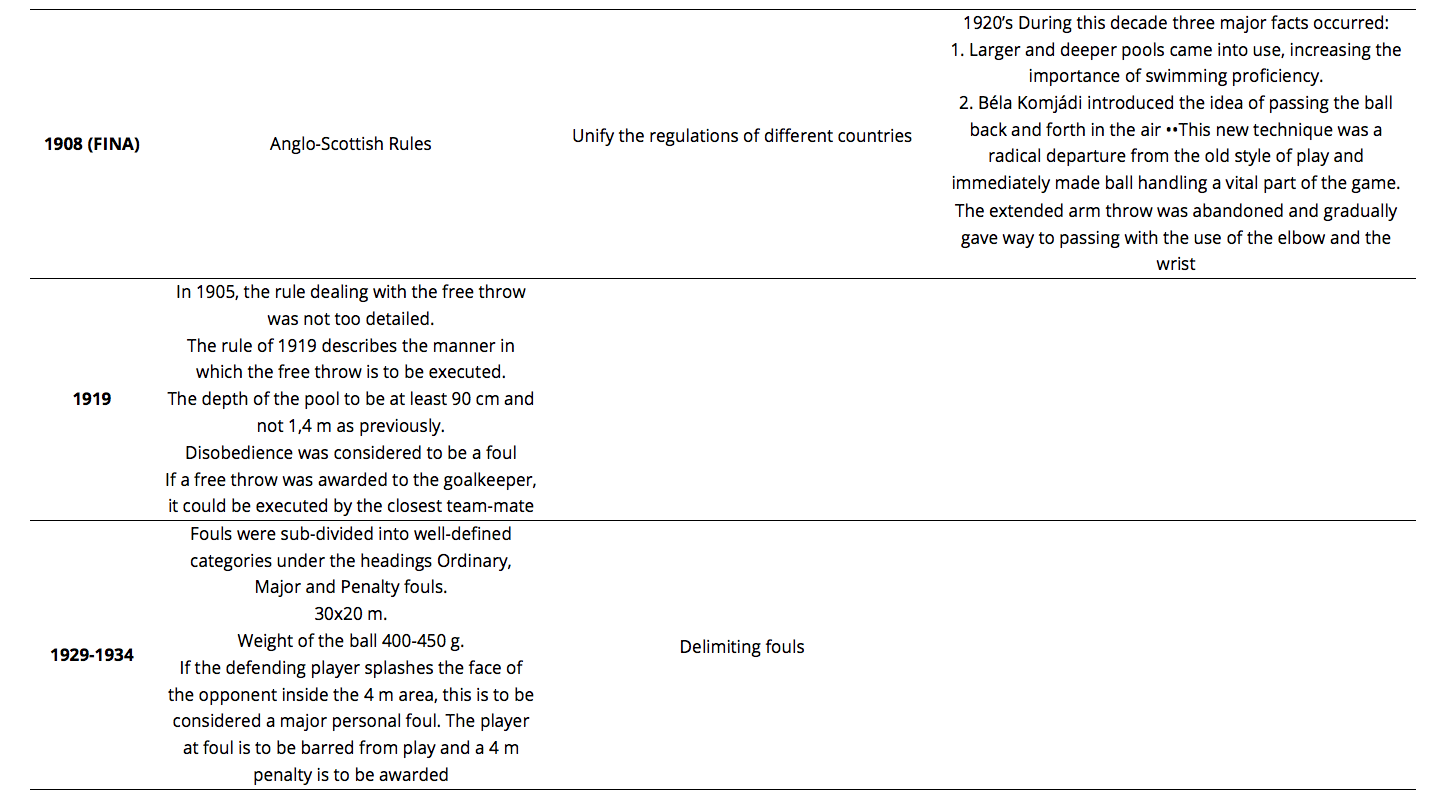

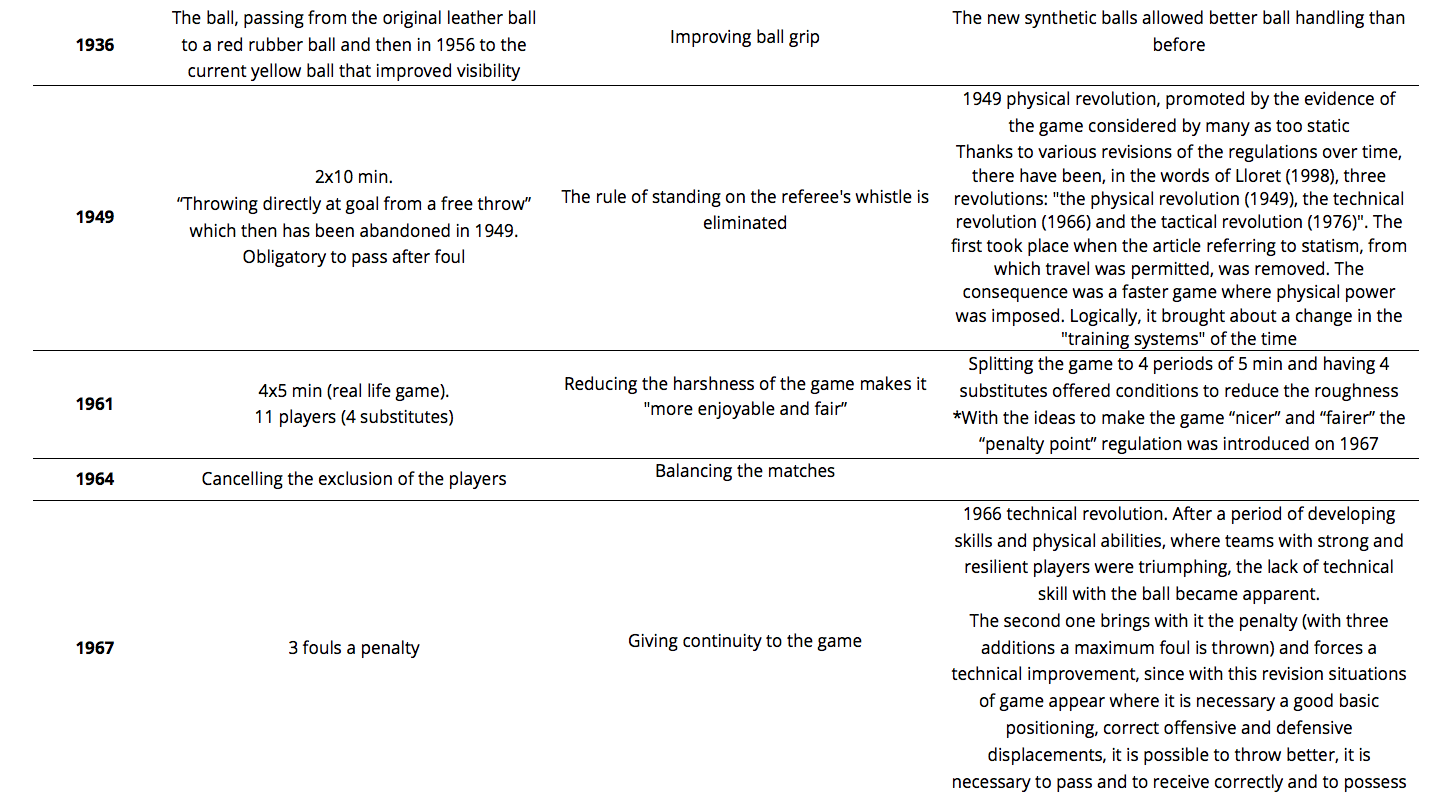

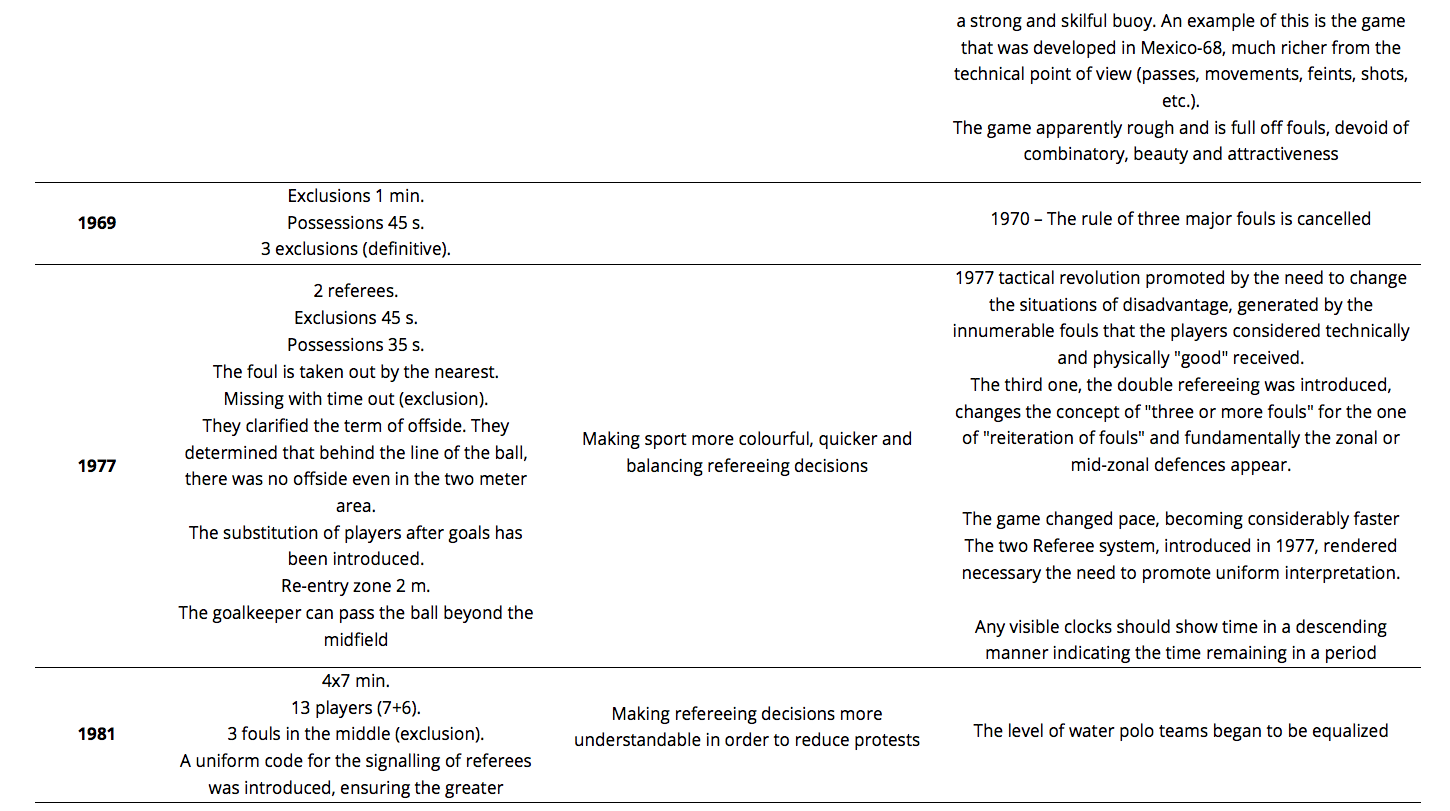

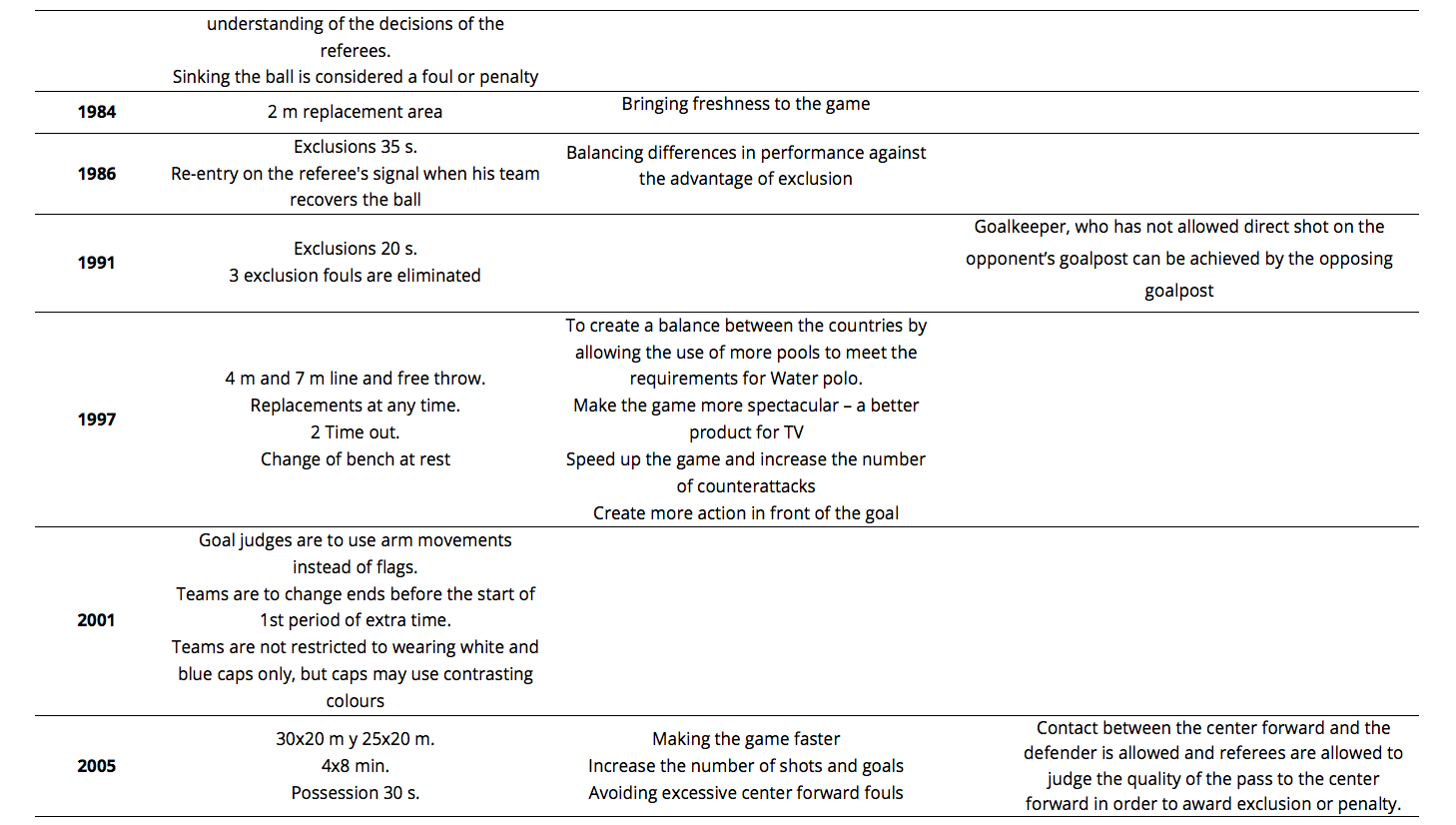

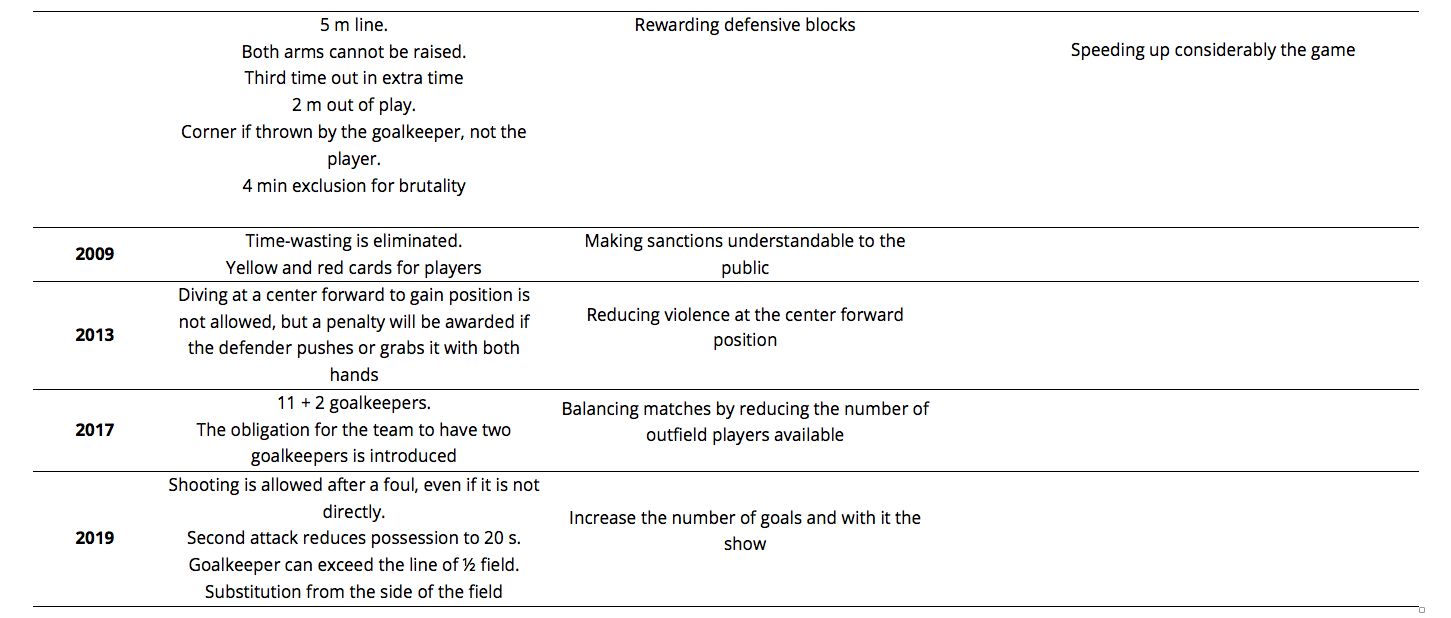

As in many other sports, throughout its 150 years of history, almost all aspects of the game have changed. Therefore, as can be seen in Table 2, rules, objectives and results achieved are explained.

Evolution of water polo rules trough the history.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe the origin and evolution of the different regulations in water polo that have existed throughout its almost one hundred and fifty years of history and its possible influence on the game dynamics.

However, to do so, it would be relevant to know whether the regulatory changes in this sport differ from or are similar to those in other modalities. Therefore, if we look at the existing literature, regulatory changes in different sports have occurred, as in water polo, throughout history, for several reasons. The first regulations were born to be able to play matches between different populations, to safeguard the integrity of the sportsmen and women, as well as to limit the actions and possibility of cheating in sport. Especially with the appearance of sports betting and the purchase of results such as those reported, in football matches by Liu, Dai, & Wang (2019), athletic races and other modalities. Other modifications arose to avoid or prevent what athletes, trainers and spectators understood as injustices (Kerr & Obel, 2015), as was the case of the modification of the score and composition of judges in gymnastics after a bad score for a great exercise and giving value to the show as a precursor of new regulatory modifications. Also increasing the participation of athletes at school age by modifying some rules such the triple line in minibasket (Arias, Argudo, & Alonso Roque, 2012) or the score in Basque pelota (Usabiaga & Castellano, 2014). As well as the demilitarisation of certain sports such as pentathlon (Heck, 2013). While other regulatory changes have emerged thanks to technical advances, such as improved materials, the case of the implemented mobile. For example, with the improvement of the leather of water polo balls, increased resistance and manageability. After their appearance, changes were seen in the game, leading to the implementation of regulatory changes that allowed players to pass the ball to each other (Rajki, 1958). Similar changes in football led to changes in team play and the need to implement new rules such as offside (Olivós, 1992). Finally, and thanks to technological advances, such as electronic scoreboards in fencing or taekwondo (Moenig, Cho, & Song, 2012), improved protectors, the introduction and comfort of boxing gloves (Vamplew, 2007), etc., made it possible to modify training systems and therefore competition, so that scores had to be adapted and previously banned actions allowed in pursuit of the integrity of the contestant.

If we look specifically at the field of water polo, there is evidence of a previous study by Madera et al. (2017), who analysed the influence of the rules on the game according to the types of structural and functional changes in the rules. They found a higher number of total goals and winning teams by increasing the duration of the match from 28 to 32 minutes, although the losers continued to score (probably the losing teams did not adapt as well to these changes in the duration of the game). However, total goals' difference, goals' difference/total goals ratio, and goals' difference/winners' goals ratio only showed increases when the length of the match increased from 20 to 28 min. Just as they appreciated that the greatest increase in goals scored occurred when implementing a possession time in attack.

In this sense, the present study tries to overcome, extending to the analyses made by Madera et al. (2017) the influence on the uncertainty generated in the game, and considering the technical-tactical aspects of the game, which gives this sport greater motor richness, increasing the equality in the game among the contenders, and therefore causing an increase in the spectacle. Therefore, the results presented here show differences in terms of the different systems and models of play used by the teams depending on the regulations in force and their implications in the game. Also, can be said that modern water polo is characterized by rapid circulation of the ball, with rapid counter attacks, powerful and precise shots to the goal, and tight duel between players play which requires that player abilities, skills, knowledge and habits are extremely high (Hraste et al., 2013). Although further research is still needed.

While these studies have always been done with the intention of finding out, which aspects of the game have the greatest bearing on performance and offering the ability to discern the situations that set successful teams apart from the rest. In this way, they provide technical managers with objective data to add to the training of the situations that are most conducive to obtaining greater performance. There is no evidence of any previous study that has analysed how the game has changed over time and the influence of regulatory changes on it. However, based on the analysis of throwing efficiency, considering the final classification of the Championship and comparing two competitions with different regulations, it is not possible to infer the existence of significant differences (Argudo et al., 2020, Argudo et al., in press). Therefore, it is possible to infer that the regulations affect all teams equally and the differences observed in this case are due to the level of the teams, their adaptation and not to regulatory modifications. This should serve to ensure that future regulatory changes are based on studies showing the suitability of the equipment.

Therefore, like the findings of previous studies, it is possible to state that throughout the history of this sport and its regulatory modifications (Lozovina & Lozovina, 2009). Three phases have been developed according to Lloret (1994): 1-Physical Pre-dominance (1948); 2-Technical Pre-dominance (1963), 3-Tactical Pre-dominance (1977), adding during these last years a last phase that can be called of economic/spectacle predominance (Lozovina & Lozovina, 2009). Although other authors such as Hraste et al., (2013) propose three more phases, each one of them standing out in terms of play:

1- The first stage of the development of the water polo is from 1869 to 1907. This stage can be marked as the search for identity and unifying the rules of water polo games. This stage is characterized by severe regulatory changes that delimited the progress of this sport. The number of players participating in the game was changed from playing without goals to including them, as well as the implements that were used, so it is not possible to provide data on the game that can be used to compare it with later regulations. This phase is the consolidation of the sport and the assimilation of the regulations by all athletes.

2- The second stage of the sport’s development the period from 1908 to 1949. This stage can be marked as a period of restructuring and internationalization of the game. The new rules contributed to a faster game (Juba, 2008). In which the players had to be physically strong and good swimmers (Lord, 2008). According to Bonačić (personal communication, November 4, 2009, mentioned in Hraste et al., 2013) the most common game system in this period was 2-1-2-1, which consisted of a defence with two central defenders in line and with one midfield defender. The primary position of midfield defender was at a distance of 7-8 m from his goalpost. During this period, with the unification of the Anglo-Scottish regulations, the use of balls that did not absorb water and deep pools, forced the appearance of the air pass and gave an advantage to swimmers (by eliminating the rule of stopping when a foul was sanctioned in 1928), so the defensive section on the attack was improved above all. This led to an increase in the number of developed throws, which made it necessary to reduce the size of the goals. In this sense, although there are no studies on the subject, we understand that the modifications in the size of the goals (of which we have evidence) were produced by the disparity of results and the excessive ease of scoring a goal. Reducing its size by improving the speed of the game and preventing the goalkeeper from touching the ground, finding a measure that maintained the balance between offensive and defensive efficiency (3 m x 0.9 m), as well as the proliferation of the sport in the USA where the pools were smaller (Rajki, 1958).

3- In the third period (1950-1969) the standardization of the ball that does not absorb water and its characteristics, allowed players to have better visibility and handling, resulting in a faster game with more goals. The new rules eliminated slow players from the game. The center forward became the organizer of the attack with an additional role of ball distributor to teammates who tried driving towards the opponent’s goalpost to gain an advantage over the opposing team and ensure favourable conditions for ball reception and shooting. This stage is characterised by balancing the matches with an increase in the penalties for fouls and giving the "little ones" (skilful and fast players) an advantage over the bigger and more powerful players. The current four period’s system was introduced to reduce effort and increase rest, which led to an increase in the number of offensive situations and therefore in the number of goals scored (by both winners and losers).

4- The fourth stage covers the period from 1970 to 1986. The game tactics model changed in this stage because the new rules limited the time of possession of one team to 45 seconds. The new rule of re-entry after one minute of exclusion influenced the development of tactics in this type of situation, both offensive and defensive, especially in certain positions. This stage is characterised by an attempt to make the rules easier and more understandable or interpretable (a circumstance that was favoured by the introduction of double arbitration). Likewise, and once the physical primacy has been overcome, the game becomes much more colourful. The skill of the players develops technical aspects such as feinting, dribbling, etc. With the increase of the mobility of the players in attack, the first tactical defensive situations (zone) and offensive ones begin. At the beginning of the 70, the duration of the matches is increased to 4x7 min and the time of attack of the teams is limited, appreciating a drastic increase of the goals scored and reducing initially the difference between winners and losers. However, with the introduction of possession time at 35 s (1977) the difference in goals scored between winners and losers (4.79) according to Madera et al (2017) increases. This fact is not appreciated again until the next modification of the possession time to 30 s. This fact may have been due to the modification in the duration of the temporary exclusion situations in which the reduction of their duration has caused a greater efficiency in them among the winning teams (Argudo, Ruiz, & Abraldes, 2010).

5- The fifth stage covers the period from 1987 to 2012. This stage can be marked as a high intensity game. Professionalism of water polo at this stage increased the volume and intensity of training. The physical workout is dry for strength development and the daily double training sessions. At this stage the development of the game of water polo, as it is understood today, began to be consolidated by the appearance of new tactical situations and by the definitive establishment of double refereeing. The balance between the teams increases and therefore there is a decrease in offensive situations, which is why all the subsequent changes in recent years have sought to increase the spectacular nature of the sport, the television interest and the entry of sponsors that increase the economic resources of the clubs and the professionalization of the current sport. Initially there was an increase in the importance in the game of temporary exclusions, reaching at least 80% of the goals scored per game. During the last years of this stage, scoring efficiency has decreased, as has the difference between winners and losers (García-Marín, 2009; Madera et al., 2017).

6- The sixth stage of changing rules will cover the period from 2013 to 2020. During this period, the rule changes will probably improve the structure of the water polo game with the aim of trying to establish equilibrium between attack and defence phases. During the last few years, some aspects of the game have been modified, leading to an increase in the penalty (Argudo, Ruiz-Barquín, & Borges, 2016), a greater number of shots, a decrease in the efficiency of the counterattacks and a decrease in the influence of temporary exclusions on the final results of the matches. However, a significant change in the nature of the game has not been appreciated until the current changes to which time should be left to check their influence on the game (Argudo, Ruiz, & Abraldes, 2010, García-Marín, 2009; García-Marín & Argudo 2017a, 2017b).

It is also important to note that the regulatory changes that have taken place over the last 7 years aim to reduce the roughness of the game and the number of fouls penalised, which according to Hraste et al. (2013) are three times those penalised in football, four times those in basketball and twelve times those in hockey. What is the aim of this reduction? Simply because there is evidence that 60% of fouls in elite matches are provoked with the intention of wasting time in the transition phase. Therefore, in some international competitions (European Junior Championship 2014), FINA tried to convert ordinary fouls into simple temporary exclusions, but the idea did not prosper and this modification was abolished before it was approved.

Once we know the changes made to date as shown in Table 2, we can say that the normative changes have always lagged behind what is happening in the game. For example, the sanction of the penalty shot was regulated when Francesc Castillo in the 1973 World Cup in Yugoslavia sank the goal to avoid an opponent's goal. As well as adding the sanction of a penalty against when requesting a time-out when the ball is not in possession, after the 2003 World Championship several coaches tried to take advantage of this gap in the regulations.

In this sense, and always according to the interpretation made by Lozovina & Lozovina (2009), on the fact that the regulatory modifications do not allow the game to develop it is true and full potential. Future studies could make use of predictive statistical models similar to those presented by Saavedra et al., (2020), who correctly classify 83.9% of the teams with the variables GB shots, action goals, time out and thefts and highlight the important work of the goalkeeper in achieving final sporting success. On the other hand, the perceptions of athletes, managers, referees, spectators (sponsors) and coaches on how changes have affected the game and its training process should be considered. Based on these contributions and on the notational analyses developed by Argudo et al. (2000, 2005a, 2005b, 2009, 2020), Lozovina et al. (2009, 2019a, b), Lupo et al. (2010, 2012, 2014), García-Marín et al. (2015, 2017a, 2017b) Graham and Mayberry (2014, 2016), etc., propose new modifications that are adapted to the current sports reality. For example, proposing that if a goal is scored beyond the 7m line it is worth double or that if a team receives more than 7 fouls in a quarter it is given a penalty (Lozovina & Lozovina, 2019b).

5. Conclusions

The evolution of a sport is closely related to regulatory changes over time. Any change in them affects the work of coaches, readapting training systems, and players, assimilating the possible variations that these imply on the game dynamics in order to remain competitive. Likewise, these modifications must seek a greater showiness that attracts more practitioners and spectators and, therefore, greater income from sponsorship for official institutions, clubs and athletes.

Many regulatory changes have been made over the years in Water polo. However, there is no scientific evidence of their effects on the game dynamics. There are hardly any studies that have analysed the before and after of a regulation modification. Therefore, it would be very interesting to be able to discuss the suitability of the modifications to be proposed and to collaborate with the federative technical managers for their possible application and thus, to be able to empirically validate the consequences of these new rules on the playing action in water polo.

In any case, we can say that the rules of water polo are alive and well and that they adapt to the changes in the game as time goes by. The current rules are in line with the health situation, trying to reduce the exposure and contact of players and officials to the merely sporting, thus adapting the refereeing to these facts (De Ara, personal communication, 3 November 2020). Referees also believe that the future of water polo will be associated with video refereeing, the law of advantage (which allows for fluid, fast, dynamic play with many chances to score) and the protection of offensive play from defensive play (De Ara, personal communication, 3 November 2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Argudo, F. M. (2000). Modelo de evaluación táctica en deportes de oposición con colaboración. Estudio práxico del waterpolo. Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, España.

Argudo, F. M., Alonso, J. I., Fuentes, F. & Ruiz, E. (2005a). Polo Análisis v1.0 Banquillo. Software para la cuantificación de las acciones de los jugadores de waterpolo en tiempo real. En F. M. Argudo, S. Ibáñez, E. Ruiz y J. I. Alonso, Softwares aplicados al entrenamiento e investigación en el deporte (pp. 187-194). Sevilla: Wanceulen.

Argudo, F. M., Alonso, J. I., & Fuentes, F. (2005b). Computerized registration for tactical quantitative evaluation in water polo. Polo partido v1.0. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium Computer Science in Sport. Croatia.

Argudo, F. M., García, P., Borges, P. J., & Sillero, E. (2020). Effects of rules changes on shots dynamics in Water polo World Championship 2003-2013. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20(2), 800-809. doi:10.7752/jpes.2020.02114

Argudo, F. M., García-Marín, P., Borges-Hernández, P. J., & Ruiz-Lara E. (in press). "Influence of rule changes on shooting performance in balanced matches between two European Water polo Championship". International Journal of Performance analysis. doi:10.1080/24748668.2020.1846111

Argudo, F. M., Ruiz, E., & Abraldes, A. (2010). Influencia de los valores de eficacia sobre la condición de ganador o perdedor en un mundial de Waterpolo. Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 17, 21-24.

Argudo, F. M., Ruiz, E., & Alonso, J. I. (2009). Were differences in tactical efficacy between the winners and losers teams and the final classification in the 2003 water polo World Championship? Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 4(2), 142-153. doi:10.4100/jhse

Argudo, F. M., Ruiz-Barquín, R., & Borges, P. (2016). The Effects of Modifying the Distance of the Penalty Shot in Water Polo. Journal of Human Kinetics, 54(1), 127-133. doi:10.1515/hukin-2016-0041

Arias, J. L., Argudo, F. M., & Alonso, J. I. (2009). Influencia del diseño de la línea de tres puntos sobre el número de jugadoras que participan en posesión del balón y las zonas de lanzamiento en minibasket femenino. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 4(10), 49-54.

Bardin, L. (1986). El análisis de contenido. Madrid: Akal.

Castejón, F. J., Martínez, L. F., Del Campo, J., & Argudo, F. M. (2011). Análisis de la documentación para la formación de entrenadores de base en baloncesto. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 11(42), 255-277. https://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista42/artanalisis200.html

Cuddon, J. A. (1980). The Macmillan Dictionary of Sports and Games. Ed. Macmillan Press Ltd. U.S.A.

De Ara, O. (2020). Personal comunication, November 3, 2020.

Delahaye, A. (1929). Le waterpolo. Anvers: Imprenta Van Montfort.

Donev, Y., & Aleksandrović, M. (2008). History of rule changes in water polo. Sport Science, 1(2), 16-22.

Flick, U. (2004). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata.

García-Marín, P. (2009). Evaluación cuantitativa de la desigualdad numérica temporal simple con posesión mediante observación sistemática en waterpolo. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, España.

García-Marín, P., & Argudo, F. M. (2017a). Water polo: Technical and tactical shot indicators between winners and losers according to the final score of the game. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 17(3), 334–349. doi:10.1080/24748668. 2017.1339258

García-Marín, P., & Argudo, F. M. (2017b). Water polo shot indicators according to the phase of the championship: Medallist versus non-medallist players. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 17(4), 642–655. doi:10.1080/24748668.2017.1382215

García-Marín, P., Argudo, F. M., & Alonso, J. I. (2015). The game action of the power play in water polo by periods. RETOS. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 27, 14-18.

Graham, J., & Mayberry, J. (2014). Measures of tactical efficiency in water polo. Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports, 10(1), 67-79. doi:10.1515/jqas-2013-0127

Graham, J., & Mayberry, J. (2016). The ebb and flow of official calls in water polo. Journal of Sports Analytics, 2(2), 61-71. doi:10.3233/JSA-160019

Heck, S. (2013). Modern Pentathlon at the London 2012 Olympics: Between Traditional Heritage and Modern Changes for Survival. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 30(7), 719-735. doi:10.1080/09523367.2013.782485

Hraste, M., Bebić, M., & Rudić, R. (2013). Where is today’s water polo heading? An analysis of the stages of development of the game of water polo. NAŠE MORE: znanstveno-stručni časopis za more i pomorstvo, 60(1-2), S17-22.

Iguarán, J. (1972). Historia de la natación antigua y moderna de los Juegos Olímpicos. Tolosa: Industria gráfica Valverde.

Juba, K. (2008). A short history of water polo. Luxembourg: LEN.

Kerr, R., & Obel, C. (2015). The disappearance of the perfect 10: Evaluating rule changes in women's artistic gymnastics. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 32(2), 318-331. doi:10.1080/09523367.2014.974031

Krippendorff, K. (1997). Metodología de análisis de contenido: teoría y práctica. Barcelona: Paidós.

Liu, Z., Dai, J., & Wang, B. (2019). Bribing Referees: The History of Unspoken Rules in Chinese Professional Football Leagues, 1998–2009. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 36(4-5), 359-374. doi:10.1080/09523367.2019.1581173

Lloret, M. (1994). Análisis de la acción de juego en el Waterpolo durante la Olimpiada de Barcelona-92. Tesis Doctoral. Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, España.

Lloret, M. (1998). Waterpolo. Técnica, táctica y estrategia. Barcelona: Gymnos.

Lord, C. (2008). Aquatic 1908-2008. Lausanne: Federation Internationale de Natation.

Lozovina, M., & Lozovina, V. (2009). Attractiveness lost in the water polo rules. Sport Science, 2(2), 85-89.

Lozovina, M., & Lozovina, V. (2019a). Why introduce a bonus for ordinary offense in water polo. Sport Science, 12(Suppl) 7-13.

Lozovina, M., & Lozovina, V. (2019b). Proposal for changing the rules of water polo. Sport Science, 12(Suppl) 14-26.

Lupo, C., Capranica, L., & Tessitore, A. (2014). The validity of the session-RPE method for quantifying training load in water polo. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 9(4), 656-660. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2013-0297

Lupo, C., Condello, G., & Tessitore, A. (2012). Notational analysis of elite men´s water polo related to specific margins of victory. Journal of Sports Sciences & Medicine, 11(3), 516-525.

Lupo, C., Tessitore, A., Cortis, C., Minganti, C., & Capranica, L. (2010). Notational analysis of elite and sub-elite water polo matches. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(1), 223-229. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c27d36

Madera, J., Tella, V., & Saavedra, J. M. (2017). Effects of rule changes on game-related statistics in men’s water polo matches. Sports, 5(4), 84. doi:10.3390/sports5040084

Moenig, U., Cho, S., & Song, H. (2012). The Modifications of Protective Gear, Rules and Regulations during Taekwondo's Evolution–From its Obscure Origins to the Olympics. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(9), 1363-1381. doi:10.1080/09523367.2012.691474

Navarro, P. & Díaz, C. (1995). Análisis de contenido. En Delgado, J. M., & Gutiérrez, J. (Eds.). Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales (pp. 177-224). Madrid: Síntesis.

Olivós, R. (1992). Teoría del fútbol. Sevilla: Wanceulen.

Rajki, B. (1958). Waterpolo. London: Museum Press.

Ruiz-Lara, E., Borges-Hernández, P., Ruiz-Barquín, R., & Argudo-Iturriaga, F. M. (2018). Analysis of time-out use in female water polo. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 13(1), 1-8. doi:10.14198/jhse.2018.131.01

Saavedra, J. M., Pic, M., Lozano, D., Tella, V., & Madera, J. (2020). The predictive power of game-related statistics for the final result under the rule changes introduced in the men’s world water polo championship: a classification-tree approach. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 20(1), 31-41. doi:10.1080/24748668.2019.1699767

Usabiaga, O. & Castellano, J. (2014). Efecto del cambio de reglas en pelota vasca escolar. (Effect of rule changes in school-league basque pelota). Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 9(27), 243-250.

Vamplew, W. (2007). Playing with the rules: Influences on the development of regulation in sport. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 24(7), 843-871. doi:10.1080/09523360701311745

Vigarello, G. (1988). Une histoire culturelle du sport. Techniques d'hier et d'aujourd'hui. Paris: Revue EPS - Robert Laffont.

Author notes

* Autor para la correspondencia. Email: quico.argudo@uam.es. Teléfono: +34 914 972 884.

Additional information

HOW TO CITE: Borges-Hernández, P. J., Argudo, F. M., García-Marín, P., & Ruiz-Lara E. (2022). Origin, evolution and influence on the game of Water polo rules: over 150 years of history. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte.

ISSN: 1696-5043

Vol. 17

Num. 51

Año. 2022

Origin, evolution and influence on the game of water polo rules

Pablo JoséFrancisco ManuelPabloEncarnación Borges-HernándezArgudoGarcía-MarínRuiz-Lara

Universidad de La LagunaUniversidad Autónoma de MadridUniversidad de Santiago de CompostelaUniversidad Católica de Murcia,EspañaEspañaEspañaEspaña